Seedbed Art Residency at Greenham Common: Beccy Mccray x 101 Outdoor Arts

Visual diary and phase 2 (final artistic development, production and delivery)

Contents:

Initial Enquiry

Visual Diary, Reflections and Inspiration: Greenham Induction Weekend

Interviews Post-induction, Pre-residency

Keith Leech MBE, Chair and Founder of Hastings Jack in the Green

Lorna Richardson, Greenham Peace Camp Woman, 1982–1987

Visual Diary and Interviews: Greenham Residency

Pilot Workshop at Greenham Community Centre With Girls Aged 9-14 y/o

Witches Den!!

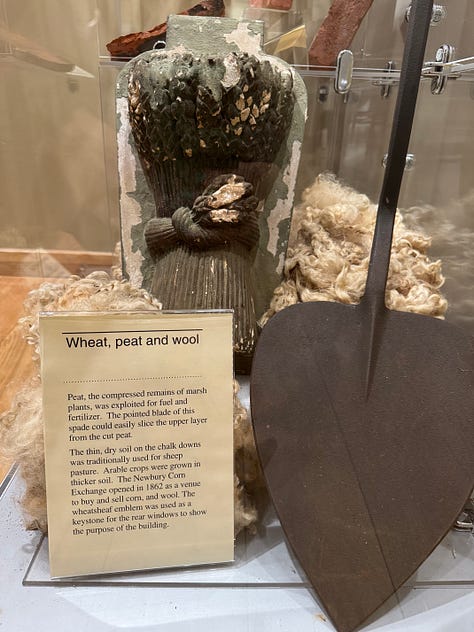

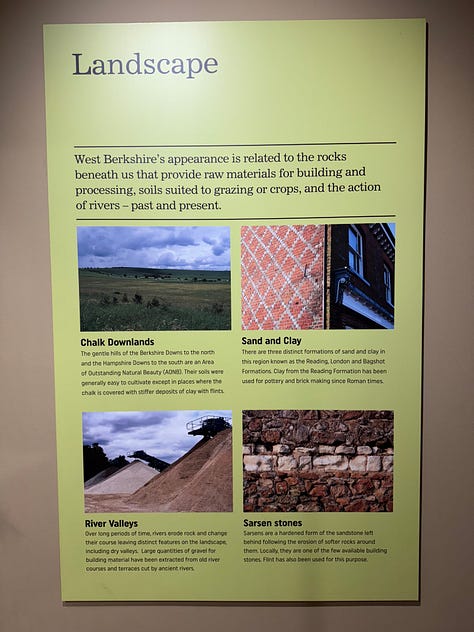

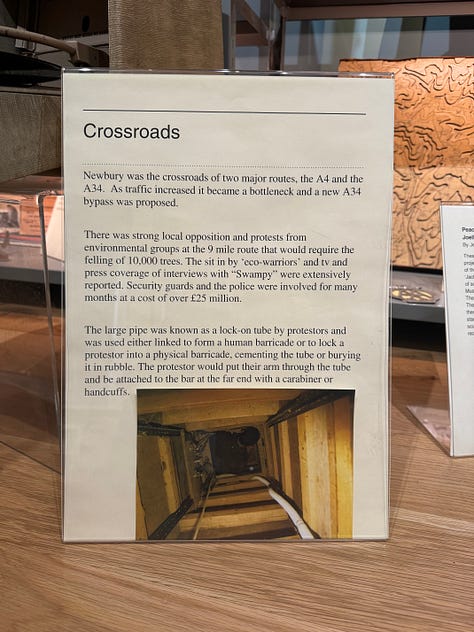

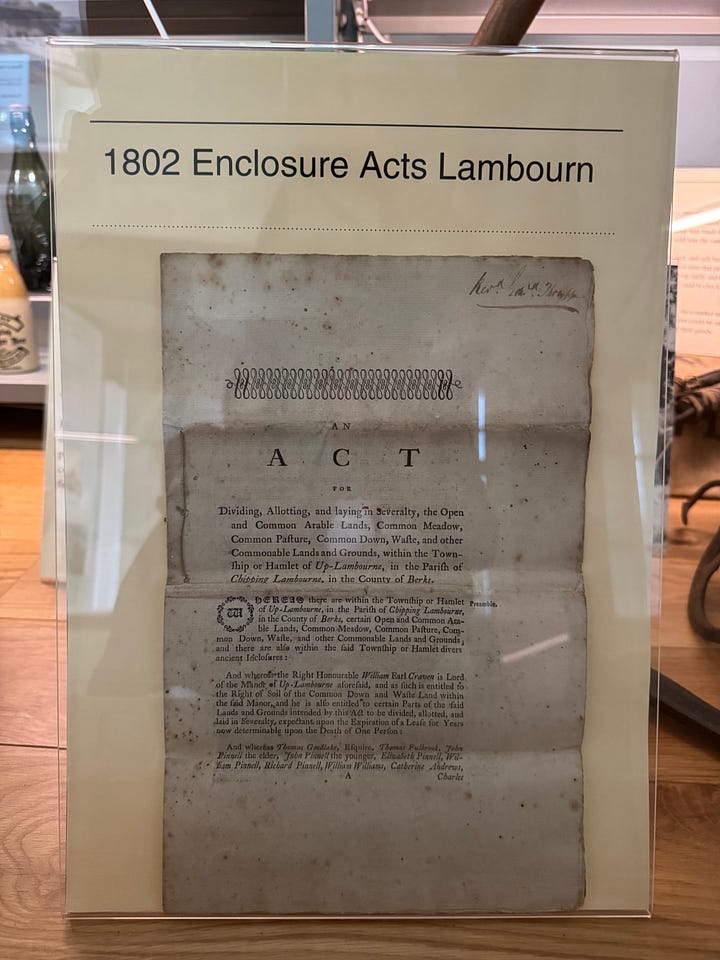

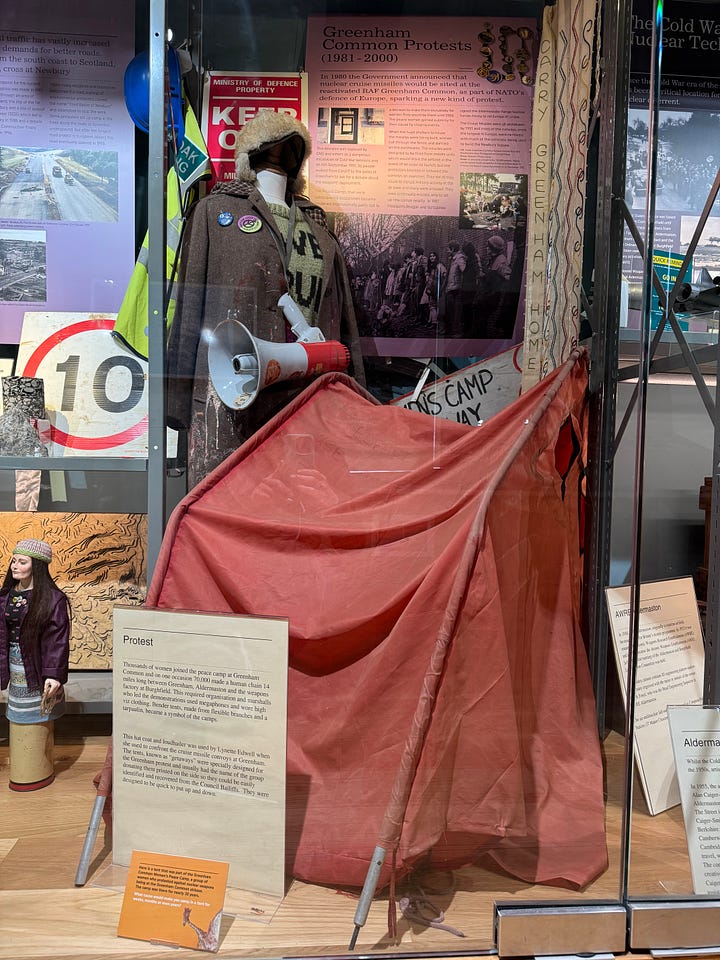

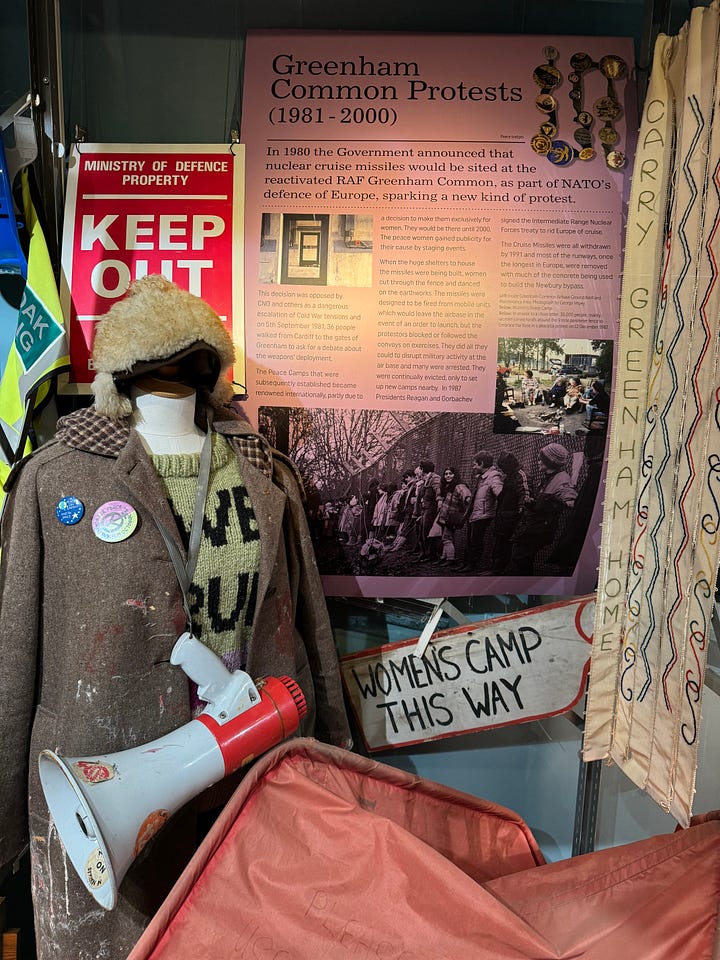

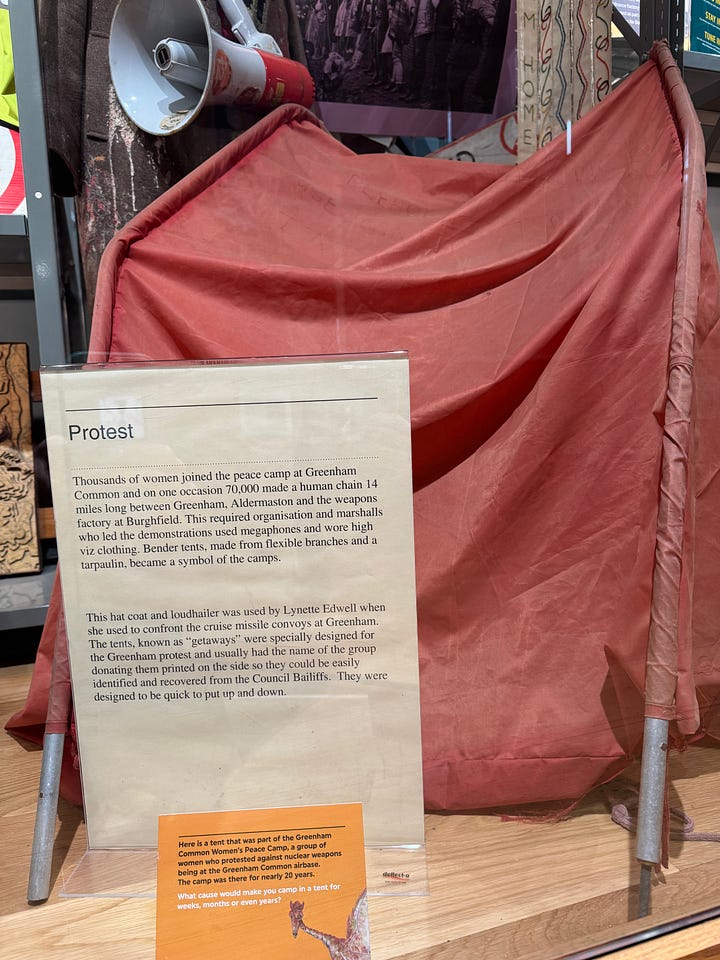

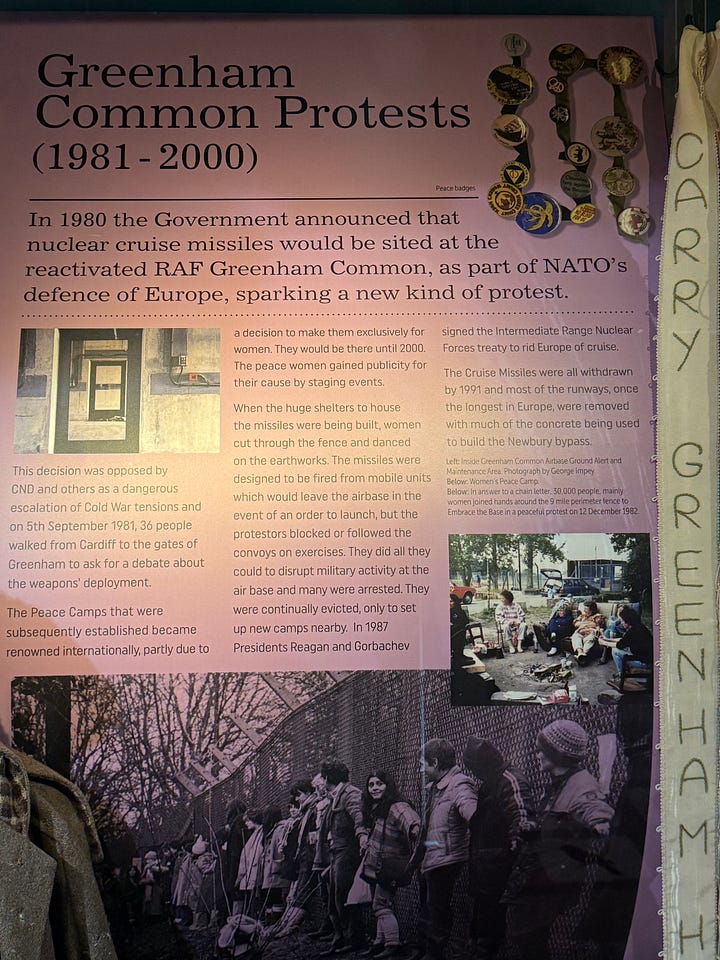

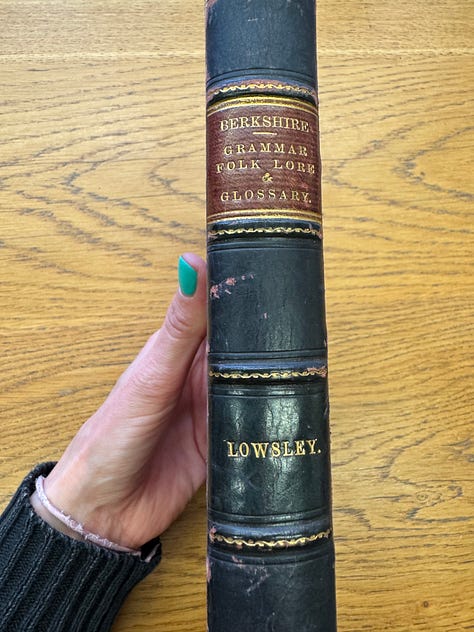

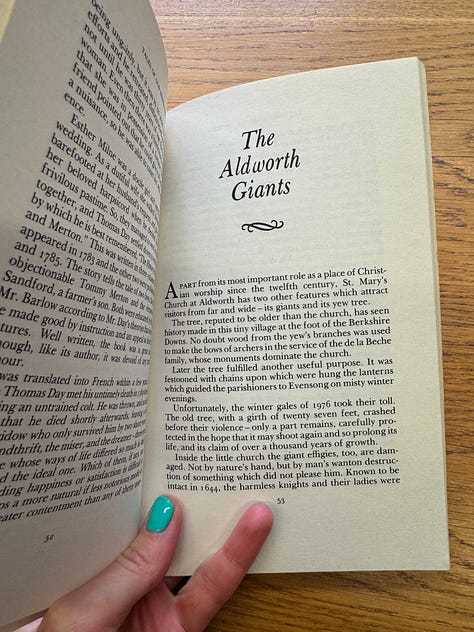

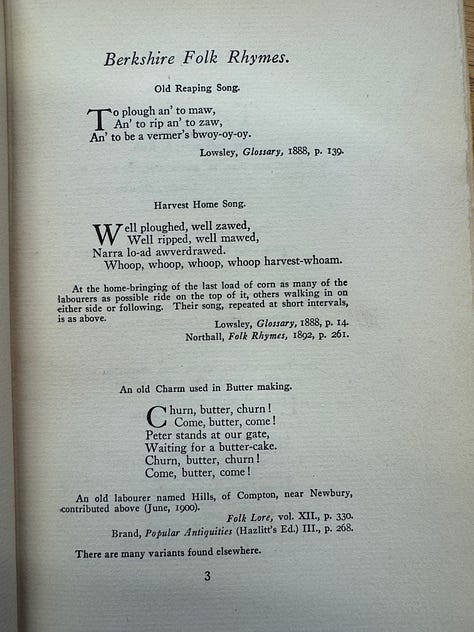

West Berkshire Museum research trip

Walking Without a Phone

Museum of English Rural Life; Interview with Dr Ollie Douglas, Curator of MERL Collections

Walking With My Camera + Experiments

Walk and Talk with Julian Cooper; Land Manager, BBOWT, Greenham Common

Tests

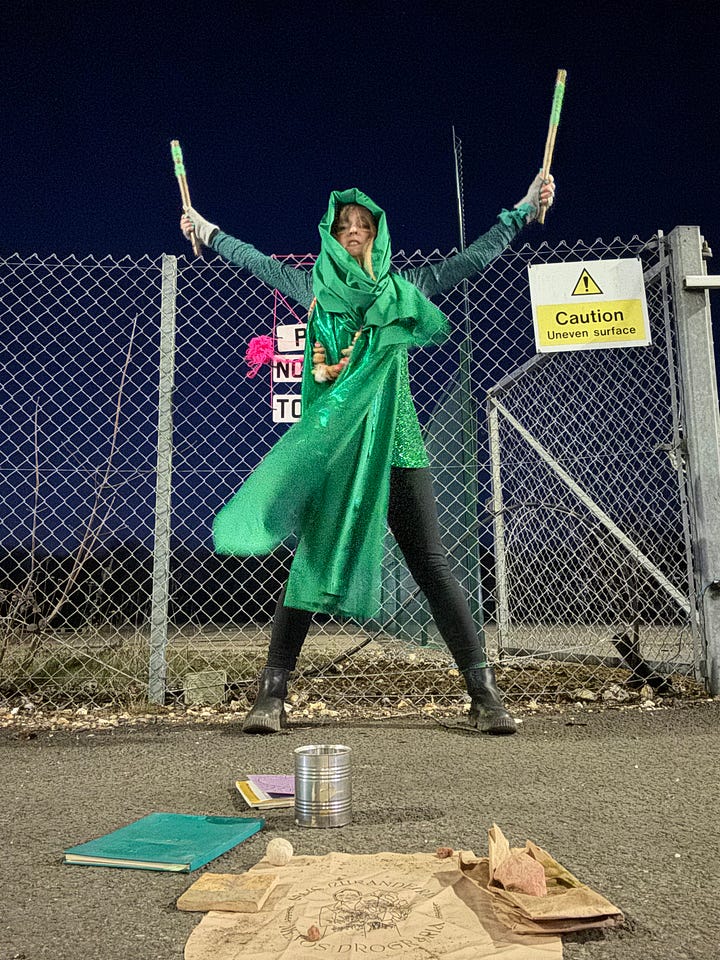

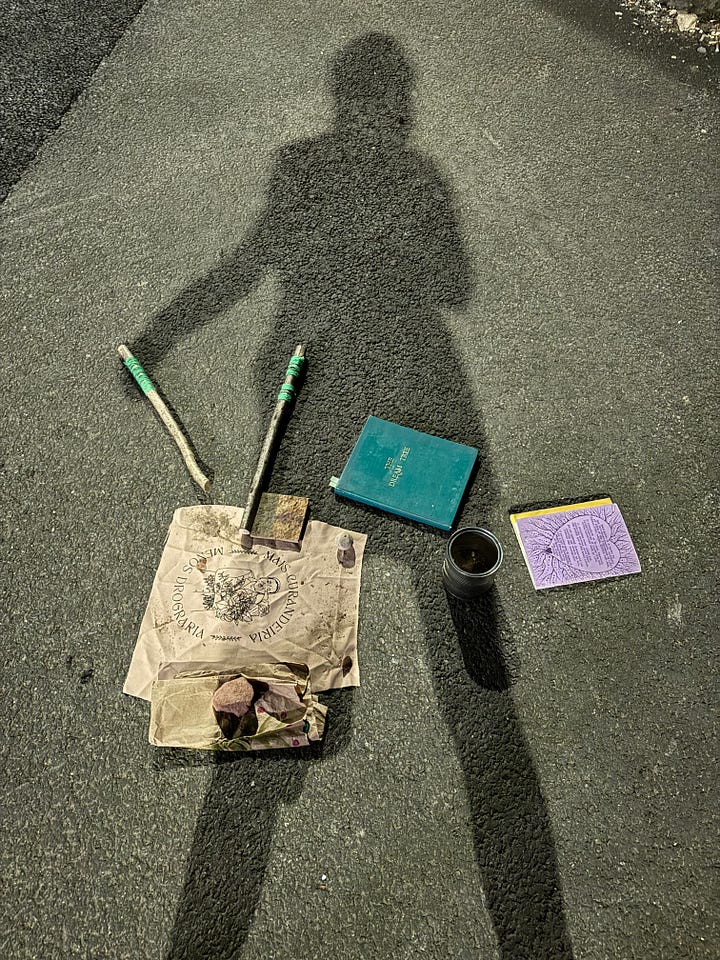

Visual Diary: Post Residency Test Shoot in Hastings

The Myth Text

🌿 The Weaving of the Green Women 🌿

CONTACT:

wwww.beccymccray.com | @beccy_mccraycray

Initial Enquiry

I grew up in Andover – just down the road from Greenham Common – in a working-class family, surrounded by the quiet intensity of protest and myth. As a kid, I absorbed the energy of the Newbury Bypass and Twyford Downs road protests, felt the pull of crop circles, Stonehenge and Avebury, where the land itself seems to speak. This project is a return to that ground, to that spirit. Greenham was always in the air. Now I’m weaving it into something new.

The "Green Woman" explores ecofeminism and resistance, inspired by the spirit of common land and the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp. Using the Green Woman - a folkloric figure tied to nature, renewal, and rebellion (subverting the character usually referred to as the “Green Man”, but encompassing idea of the crone, the hag and the green-skinned witch) - it weaves together performance, ritual, and installation to imagine new ways of connecting activism with ecological care. The work reclaims ancient rites while looking to the future, exploring how these symbols of pagan resilience and feminist defiance can create new mythologies and inspire action in the face of today’s ecological and social challenges.

‘They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds”, Zapatistas, indigenous activists

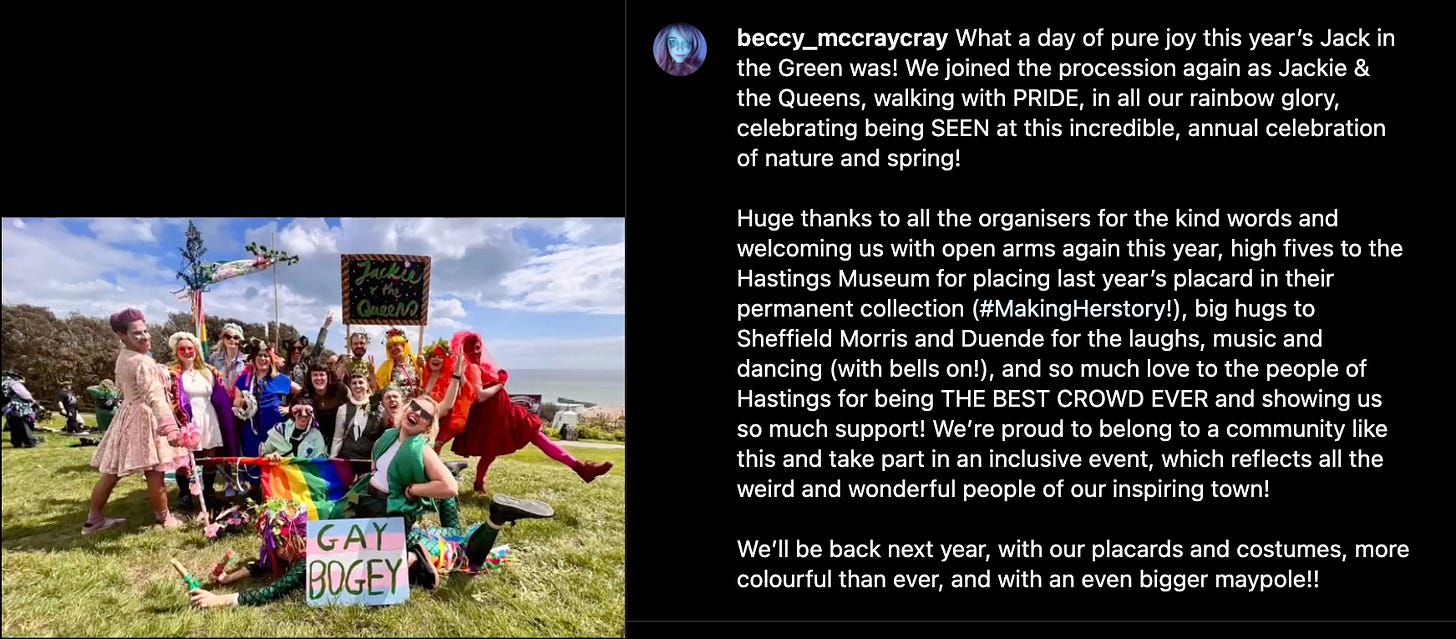

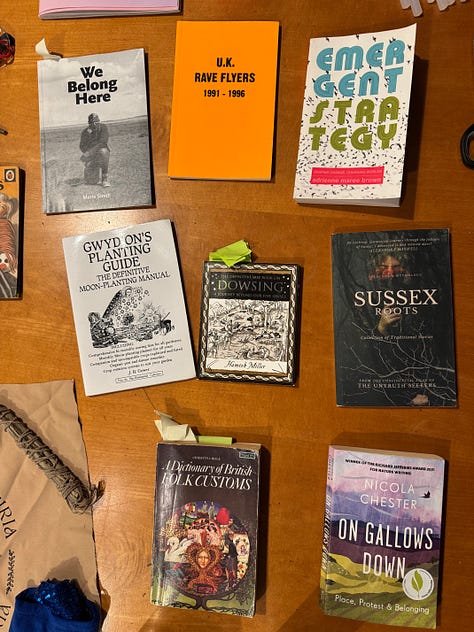

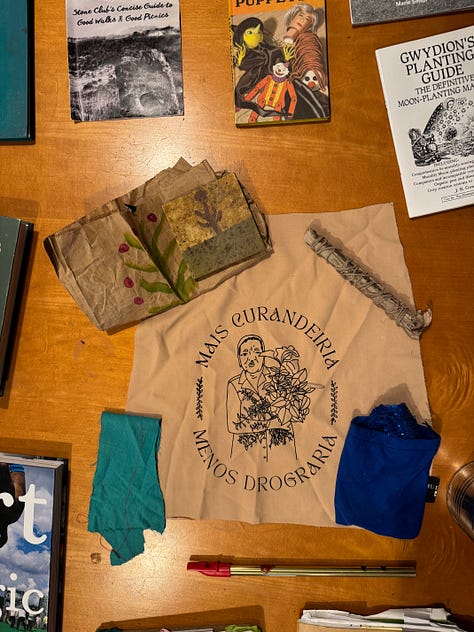

The idea builds on intersectional climate themes and research I explored in my "HAG" test artwork (see below) and British Council residency in Brazil last year, alongside my exploration of commons and land access during my New Forest National park residency, and my ongoing, active participation with the ritual year’s pagan festivals, including ‘Jack in the Green’, a Beltane (May Day) festival in Hastings, where I live.

I will partner with local activists, archivists and communities to uncover and honour Greenham’s living history, collaborating with Greenham Women, and working class communities who often feel excluded from art, culture and nature, alongside curators, land managers and ecologists, connecting the work to the land’s heritage, natural cycles and ecosystems.

The Green Woman is an invitation to think, act, and collaborate - a way to inspire reflection and conversation while making space for community participation.

Research Questions:

How can ‘Green Man/Woman’ folklore evolve into modern-day mythology and a symbol of ecofeminist art and activism?

What threads connect Greenham Common’s holistic history of activism with today’s intersectional ecological challenges?

How can participatory performances and installations create space for dialogue about nature access, renewal and resilience?

How can ancestral knowledge, ritual magic, syncretism and the creation of sacred spaces address our relationship with the more-than-human world and each other?

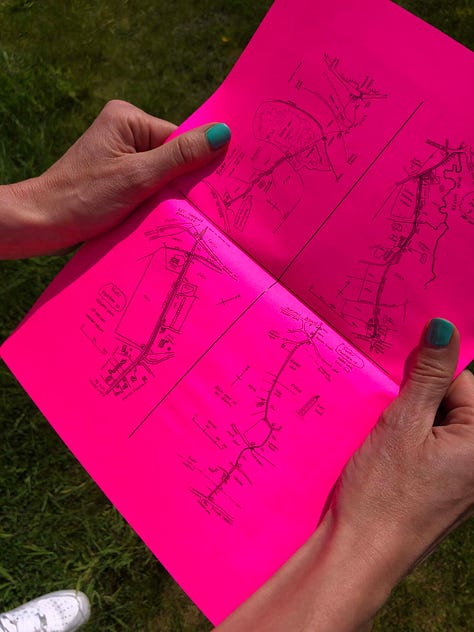

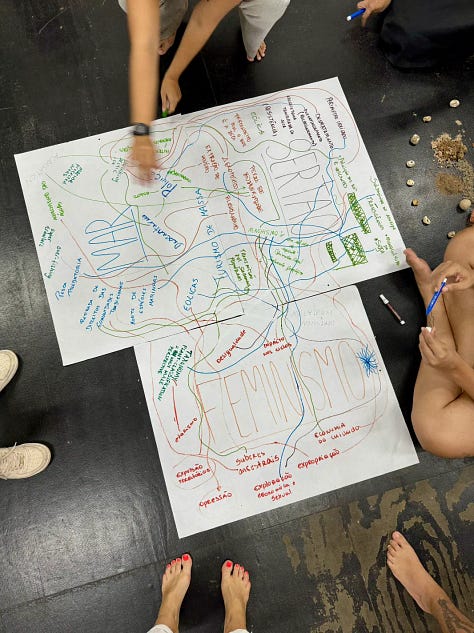

Participants and workshopping during Brazil residency with the British Council

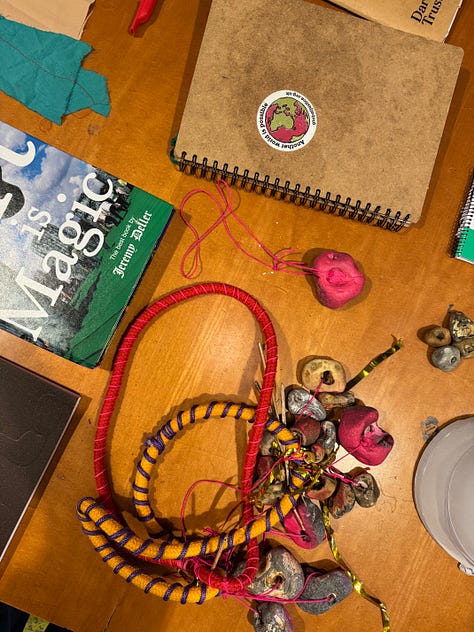

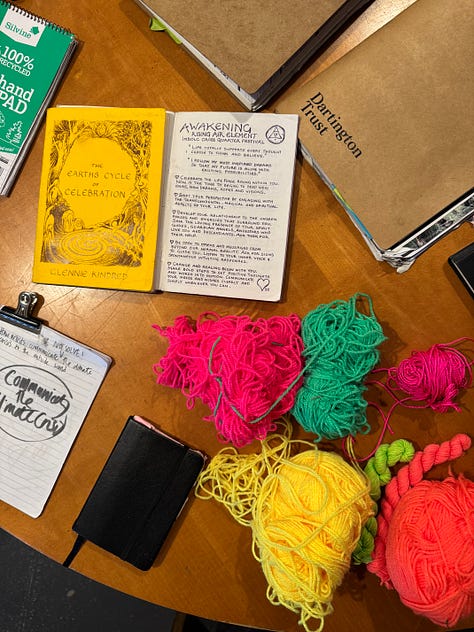

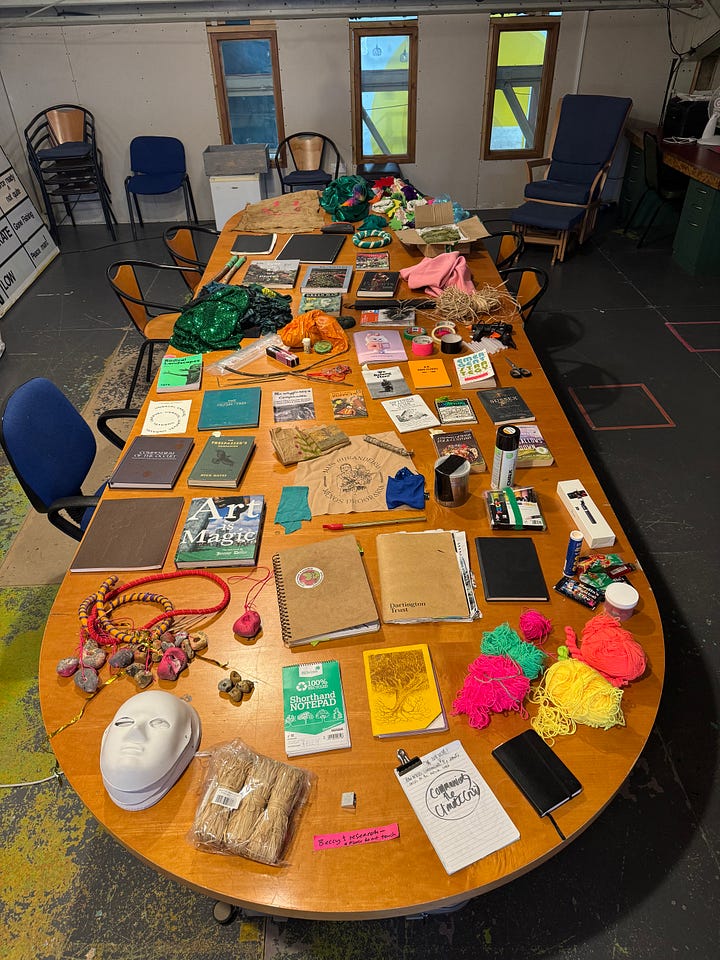

Visual Diary: Induction Weekend Reflections and Inspiration

This period was rich with insight, emotion, and provocation, grounding me in the layered, living history of Greenham Common and the peace camp that once occupied it.

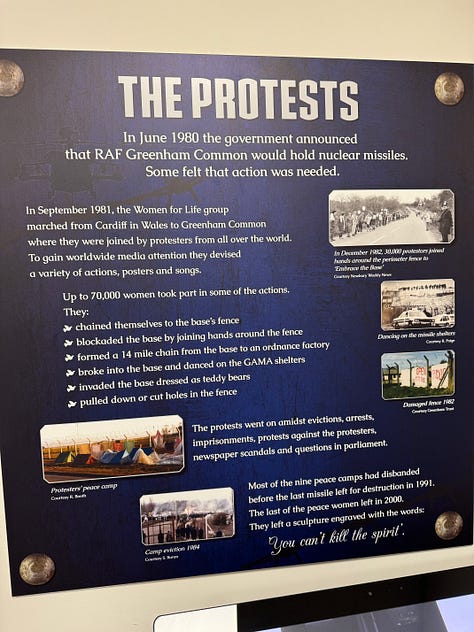

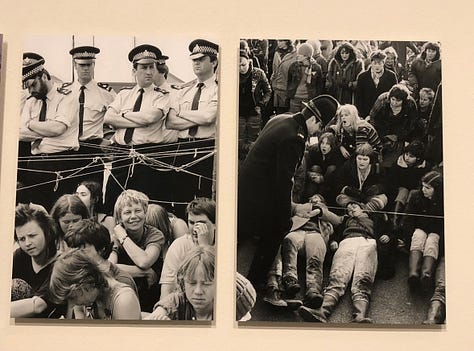

The Greenham Peace Camp was women-only – radically so. It was a response to militarisation, yes, but also a response to misogynistic systems that continually silence women and do not want us to unite. The camp became a battleground not only for disarmament but for gender and land justice. The press vilified them. The state ignored or punished them. But the community of women remained until victory was theirs.

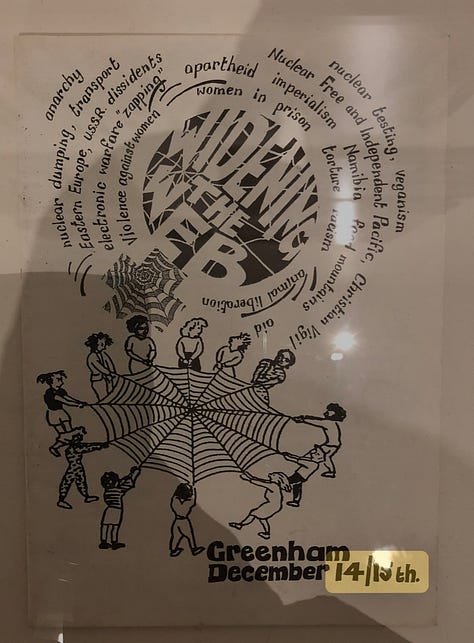

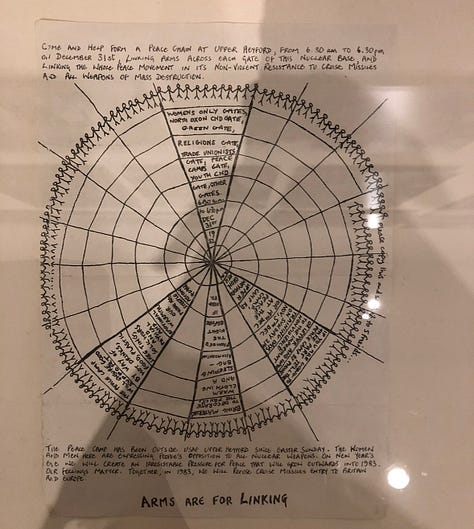

I was particularly struck by the way the camp was described as a “university of ideas” – an evolving place of progressive debate, difference (‘testing ideas’) and collective learning. Organising was intersectional before the term became commonplace. The gates themselves spoke to diversity of approach – Green Gate for healing, ritual, and spiritual connection; Blue Gate associated with younger, working-class women and non-violent direct action. It was never a monolith, but a (pre-internet age) web – a living, breathing commons, a balance of rights, responsibility, and rebellion.

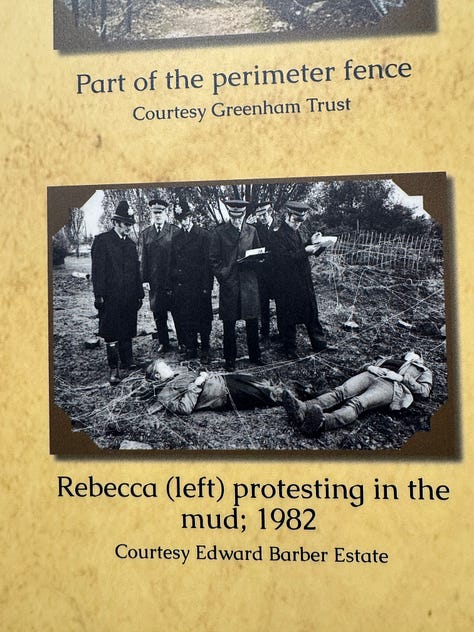

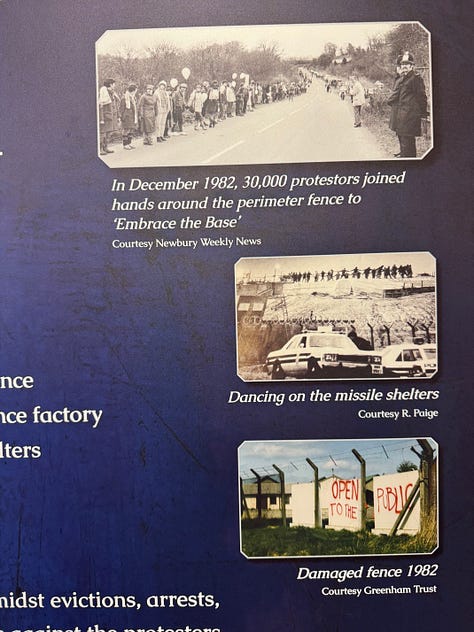

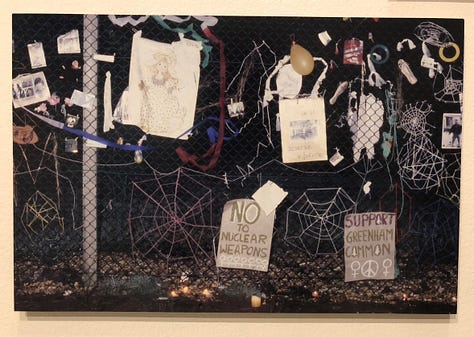

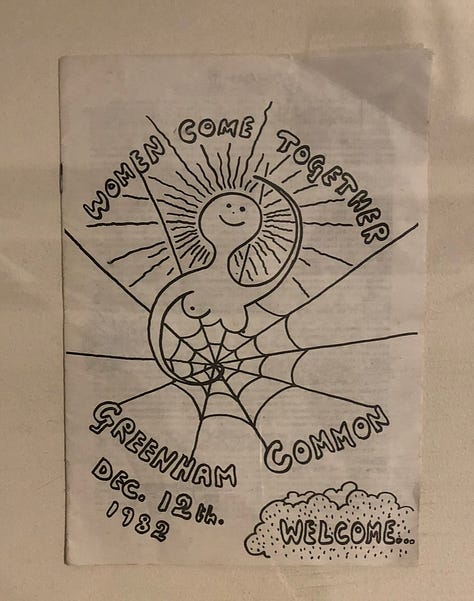

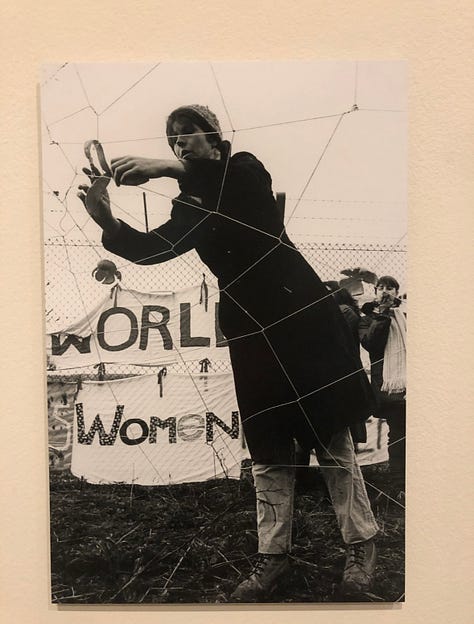

There is something deeply mythic about this place and this history. The women’s activism often took ritualistic, creative forms: walking as an act of resistance and resilience, the building of gypsy bender tents, embroidering ponchos with sigils and symbols of solidarity – lived experience embedded into the fibre and thread; dancing on missile shelters; Embrace the Base - holding hands around the military base in a 14-mile chain of defiance; breaking in and placing wild-clay goddess figures in military drawers; reclaiming barbed wire and subverting it into a symbol of resistance.

"What was a symbol of them became a symbol of us”, Lorna Richardson, Greenham Woman

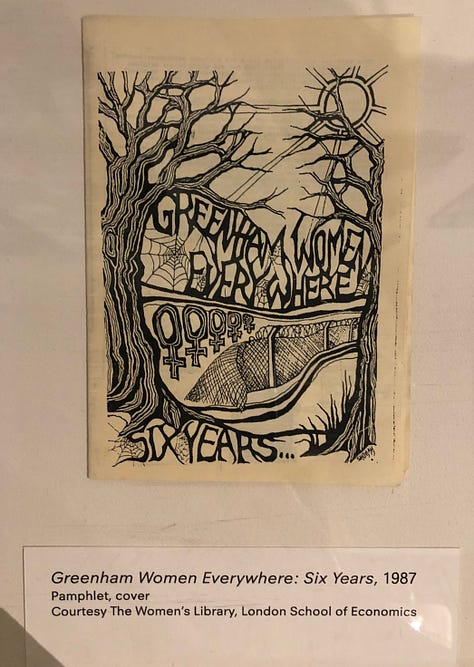

Some identified as witches. Hagstones – also commonly known as adder stones, as the hole through middle resembles the ouroboros symbol of the snake eating its own tail (adders are in fact native to Greenham Common) – were worn around necks like amulets. Embodied knowledge and land-based wisdom pulsed through their actions. Many Greenham Women saw the Common as not just a site of protest but as sacred ground of interconnectedness, to the more-than-human world and a web of women across the globe. The web became the primary sigil of the Peace Camp.

“Local actions connecting with global commons.”, Prof Katarina Navickas

The symbolism is endless. The peace women lit fires just as the gorse has always burned. Bronze Age burial mounds under the now moss-covered missile shelters contain the remains of funeral pyres. In more recent years, Star Wars filmed its rebel base scenes here. Fire is forbidden on the Common now, but smoke has always risen from this land.

“Smoke feminises the landscape”, Judy Chicago.

And so I return, again, to questions of land justice: Who belongs here and to what ends? Who decides? What does it mean to trespass when the land was never truly surrendered?

I leave the induction weekend with a strong sense that the story of Greenham needs to be told and retold until it becomes myth – until it lives in the bones of our collective memory. And the pre-internet, web-like model of networked activism and cascading information needs to be replicated. You can’t kill the spirit.

“Greenham is a model of organising – use it!” Lynette Edwell

Interviews

Keith Leech MBE, Chair and Founder of Hastings Jack in the Green

Origins, Intention & Cultural Reclamation

Keith became interested in English folk culture while studying Ecology in Wales, noticing a stark contrast between Welsh cultural pride and English cultural amnesia.

He discovered that England has one of the richest folk cultures in Europe, yet it's often uncelebrated or forgotten.

He was drawn to Jack in the Green as a unique and important British tradition, and is committed to helping it survive, grow, and evolve.

The Birth of Hastings Jack in the Green (1983)

The festival began with just 20 people, and has since become a major celebration that continues to grow. “It’s something people desired and wanted to be part of.”

Keith reflected that in the 21st century, there’s a deep hunger for traditions like these - rituals that offer connection and meaning.

“It’s all about community,” he said - people coming together, being in the moment, but also connecting with archetypes, ancestral memory, and the collective unconscious.

He also noted something vital: perhaps urban life needs Jack in the Green/The Green Man - and by extension, nature, mystery, and myth - even more than rural communities. We discussed a sense that cities have become disconnected from seasonal, sensorial and instinctual rhythms, and events like this restore a kind of ecological and spiritual grounding.

On the Green Man (and Green Woman)

The Green Man’s strength lies in his ambiguity; his origins are obscure, and that uncertainty invites personal and collective meaning. He is an archetype that can mean anything to anyone. “It’s okay not to know,” Keith said. “Mystery has become taboo, but it’s powerful. Reclaiming it is part of the magic.”

To him, the Green Man represents renewal, resurrection, the turning of the seasons, and a spirit of the woods - a symbol that crosses religious, cultural, and ecological boundaries, and aligns with his own Christian believes.

While often seen as a rural figure, Jack in the Green is an urban custom - born in the city, performed in the street. This further complicates and deepens its resonance for modern life.

Jack may not look traditionally feminine, but he still embodies fertility, as well as transformation and wildness.

The Green Lady vs The Green Woman

Heather Leech created the Green Lady - a votive figure of serenity and grace.

I honour this representation, but my vision of the Green Woman carries wilder, more complex energies: She is infused with the wild unpredictability of the Green Man. She carries the fierce resistance of the Greenham peace camp women. She pays respect to the quiet strength and sacredness of the Green Lady. She is part goddess, part resistance fighter, part hedge witch (a practitioner of folk magic associated with liminal spaces between physical and spiritual worlds, often a healer who lived on the outskirts of villages) - a living archetype, emerging from instinct, ecological memory, and communal longing.

On Folklore, Ritual & Resistance

Keith emphasised that folklore is not fixed: “We’re creating our own folklore all the time.”

Rituals like slaying the Jack are recently invented traditions and unique to Hastings - yet no less meaningful. They evolve through repetition and community, becoming new forms of embodied myth.

He noted that when you perform Jack, “you become him.” It’s not just performance - it’s embodiment, archetypal activation, a re-enchantment of the everyday.

Simply gathering in the street or on common land becomes a political act - an act of resistance, of joy, of ownership. “The person is political” (also echoed by the Greenham Women)

Keith and Heather invoked the theory of carnivalism: collective joy, revelry, and ritual as forms of cultural subversion. These are not just performances; they are temporary autonomous zones, places where new ways of being can be imagined - and remembered.

Lorna, Greenham Peace Camp Woman, 1982–1987

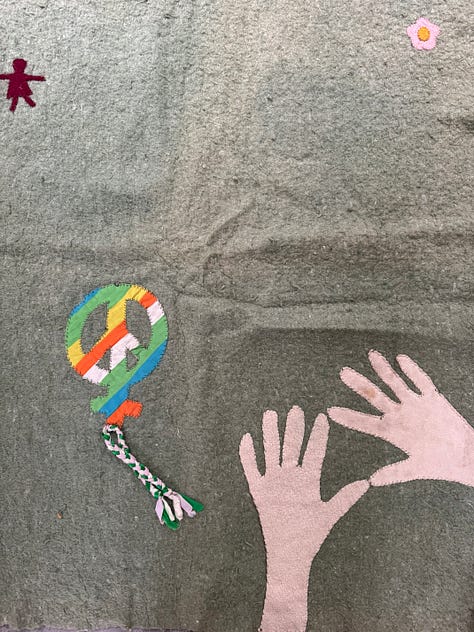

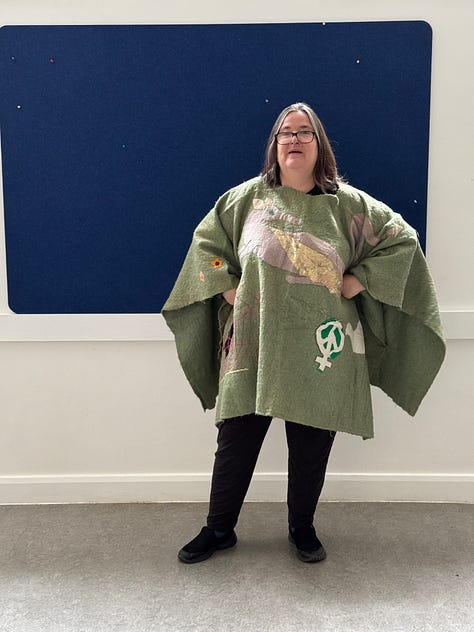

On route to 101 I met Lorna Richardson again, this time at her workplace, the Quaker Hall, Covent Garden, for a more in-depth discussion and a closer look at her hand-stitched poncho and hood.

Arrival & Activism

Lorna first arrived at Greenham aged 16, hitchhiking to the site.

She stayed until she was 21, and considers herself “still an activist now, not just then.”

Her early experience at the camp shaped her belief in agency and collective power as a young woman. “Even as a penniless teenager arriving there, I knew: I can make things happen.”

Philosophy of Peace & Resistance

“Peace doesn’t mean passive.” Lorna challenged the perception of peace as stillness or silence. She associates peace with effort, endurance, and in some ways, conflict.

Conflict was accepted as part of coexistence. “It’s OK to argue. You can disagree and still live alongside each other. Just be ready to change your mind.”

She also emphasised that critique is necessary - if handled with care.

Labour & Daily Life at Camp

Life at the camp was physically hard, repetitive, and demanding: “Build the camp. Authorities pull it down. Rebuild. Make a fire. Put it out. Repeat.”

However, these cycles of labour were grounding and contributed to a raw connection with the land. “You can’t help but be connected to nature. You’re living in the elements. You’re peeing on the ground! You have to pay attention.”

Symbolism & Rituals

Lorna’s poncho features a snake. When asked if it referenced adders,“No - it’s Eve. It’s women. It’s cunning.” The snake is a feminine, mythic symbol - but also local fauna.

Webs were a central theme at Greenham, representing interconnection and intersectionality.

However, she acknowledged that not all symbols carried deep meaning - and that’s okay. “We can let them mean what we want them to.”

Her views echo those of Keith Leech (Jack-in-the-Green) on how folk symbolism, particularly the Green Man, remains open to reinterpretation.

Art, Humour & the Trickster Spirit

Ritual, humour, and play were essential. Some examples were shadow puppet shows (featuring crows and spiders), a costumed ‘teddy bears picnic’ on the airfield runway, a ‘de-baptism’ ceremony.

Humour was used as resistance and reclamation: “They called us witches and lesbians. So we played into it. We turned it into power.”

Lorna celebrated the trickster energy of the camp - irreverent and clever.

Spirituality & Connection to Land

The camp brought together pagan beliefs: Starhawk, a visiting witch from Avebury, held rituals. There were sleep-outs at Stonehenge and walks across Salisbury Plain. Rituals, and seasonal customs were embraced.

However, there was an emphasis on the earth as the shared ground, not as an endless resource, or belonging to any one religion. “The earth connection was both practical and mystical. You became conscious of everything you used.”

Diversity Within the Camp

The peace camp was intergenerational and egalitarian.

Women moved fluidly between gates - each had its own energy: Green Gate - more spiritual. Blue Gate - younger, working-class women.

Not everyone agreed, but the collective held: “The people you don’t like might not be the same people you disagree with. You have to work together.”

Global Awareness & Indigenous Solidarity

From the start, the camp had international and indigenous connections: Namibia, Nicaragua, Canada (First Nations), Nevada (Western Shoshone). British nuclear testing sites were often on indigenous land. “People are dying now. Not just in the future.”

Legacy & Message for the Future

Her strongest advice for younger women today: “Your actions matter. What you do has consequences. You can make a difference.”

What’s stayed with her most is the web of connection: “The bond. The relationships. They’re still there.”

She spoke about rites of passage - particularly the idea of a Hag Party at 80. We talked about the TV show The Change as a rare celebration of older women and community elders. There is power in becoming the crone.

Visual Themes

Dominant palette at the camps around the Gamma Site: green and blue.

Animal imagery: snakes, crows, spiders.

Symbolic focus: webs, earth, ritual cloth.

Stitching and embroidery used both for protest and storytelling.

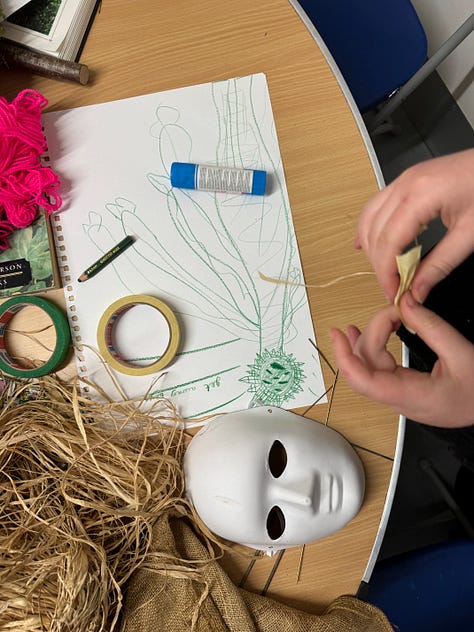

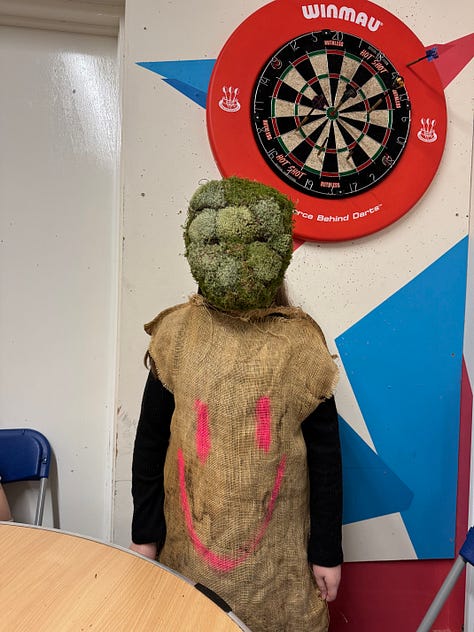

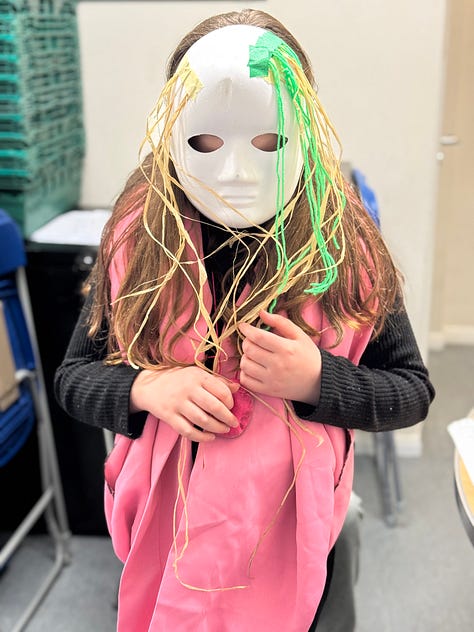

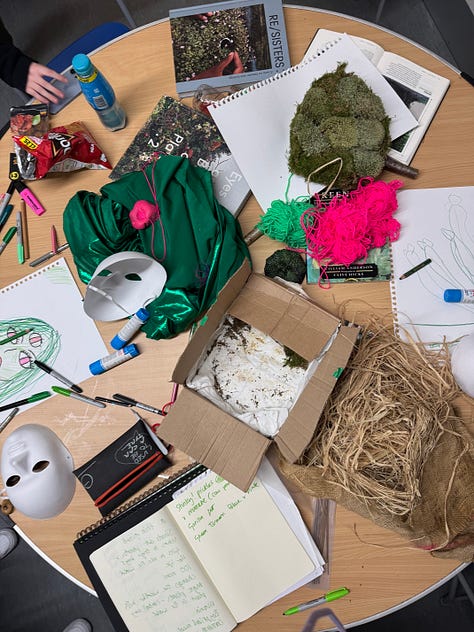

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Pilot Workshop at Greenham Community Centre With Girls Aged 9-14 y/o

Workshop Aim

This session explored how the concept of the Green Woman might resonate with girls aged 9–14 from marginalised, working class communities. It tested instinctive response, mythic recognition, and imaginative possibility. The session was play-based, exploratory, and rooted in curiosity - inviting their ideas without prescriptive framing.

Initial Associations: Festivals, Anger, Nature

When asked what festivals or carnivals mean to you, the girls responded immediately and viscerally!

“Lights”, “balloons”, “music”, “dancing”, “sex”, “twerking!”

When asked what makes you angry, their answers were consistent and deeply felt:

“Teachers”, “dads”, “male violence”, “traffic”, “chores”

Their relationship to the more-than-human world was complicated:

“Nature scares me, I like being in my bedroom.”

This early dialogue revealed a tension between the freedom they imagine and the containment they experience - a fertile space for rewilding through story, embodiment, and play.

What Do You Think of When You Hear ‘Green Woman’?

The Green Woman was unfamiliar - but highly evocative. Immediate associations included:

“Witches”

“Fiona from Shrek”

“Plants”

“Weed”

“A girl covered in leaves”

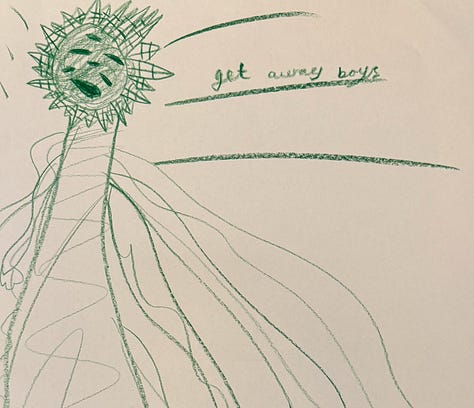

Who Could She Be? (Emerging Myth)

When asked what they’d like the Green Woman to be like, the responses were both wildly playful and symbolically rich. Together, the girls began to shape a new figure - part trickster, part goddess, part monster, part them. She was:

Colours: green, blue, and pink

Loud and leafy

Covered in green body paint or green fur, and wearing a green gown

“Her boobs are out!”

She’s strong and scary

A trickster

A thin giant

“She doesn’t like men or boys - vines shoot out of her to trap them”

She has 100 arms

“She smells of pickle” (ref the pickle factory on the industrial estate)

“She eats insects”

Controls the weather with magical plants

Comes out at sunset and “She likes fire”

Nocturnal and “Sees with her eyes closed”

These attributes map directly to themes of embodied power, nature-based agency, resistance, transformation, and being of not separate from the more-than-human - all rendered in their own language. The Green Woman is simultaneously grotesque, sacred, hilarious, and terrifying.

Engagement with Greenham Common

Most of the girls were aware of Greenham Common, but rarely used it:

One girl: “I meet my boyfriend there.”

Another: “Not allowed to go.” (parental safety fears).

Another: “Only pass through.”

One girl challenged the premise of the project itself:

“Why are you doing this in Newbury? It’s a shit hole.”

Being from nearby Andover myself, and a similar background to the girls, this resonates with my own lived experience. This question speaks to a sense of dislocation and lack of ownership over place - a challenge which The Green Woman project directly responds to through re-enchantment, myth-building, and place-based play.

Tactile & Symbolic Engagement

A highlight of the session was the introduction of divining rods. The girls were immediately engaged. They played with them freely and took some home. This tactile encounter opened up space for intuitive exploration and embodied myth-making.

The rods acted as a portal - an object of mystery and agency that bypassed language. This may be a powerful motif/tool to carry forward into further development.

Ideas Offered by the Girls

Suggested a ‘fairytale book’ featuring the Green Woman. This could offer an accessible and co-authored narrative tool for future engagement.

Expressed strong interest in maker up, costumes, and imaginative role-play. Frightening or trickster roles were particularly appealing.

Key Insights for Project Development

Myth works - especially when it’s messy, irreverent, and open to re-interpretation - emerging from our collective imagination.

Girls are eager to invent characters with power and complexity.

There's a desire for hands-on, tactile, sensory experiences over purely verbal or reflective ones.

The Green Woman must not be clean or sweet - she should be funny, dangerous, wild, and weird.

Place-making must begin with the real feelings they have about the site (e.g. fear, boredom, disconnection) before layering in new meaning.

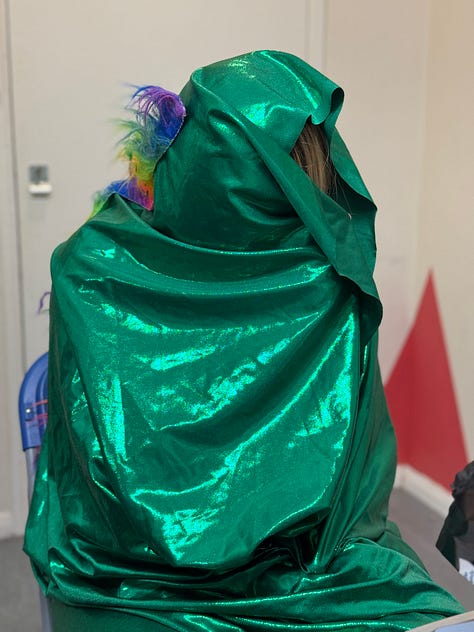

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Witch’s Den!!

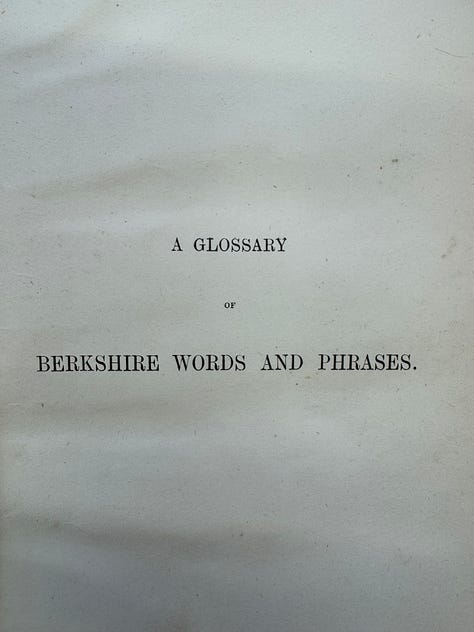

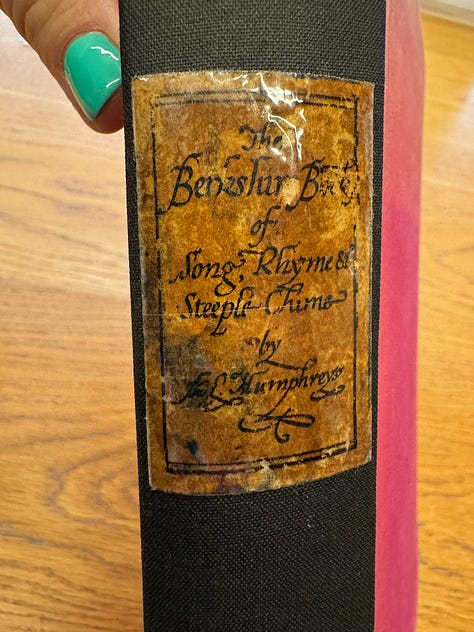

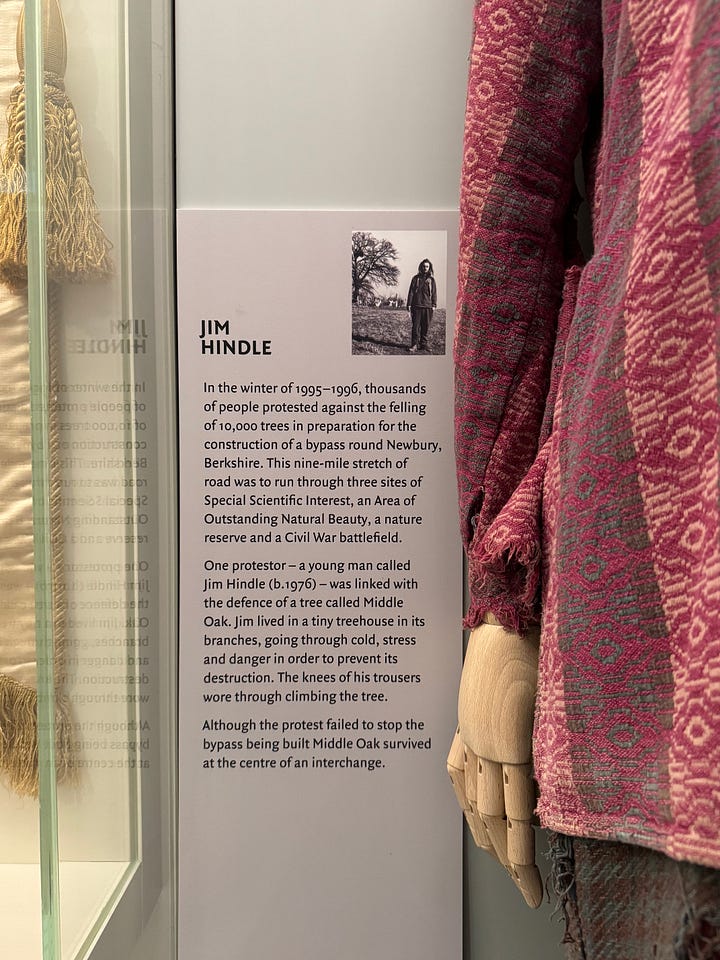

Visual Diary: Residency Week - West Berkshire Museum research trip

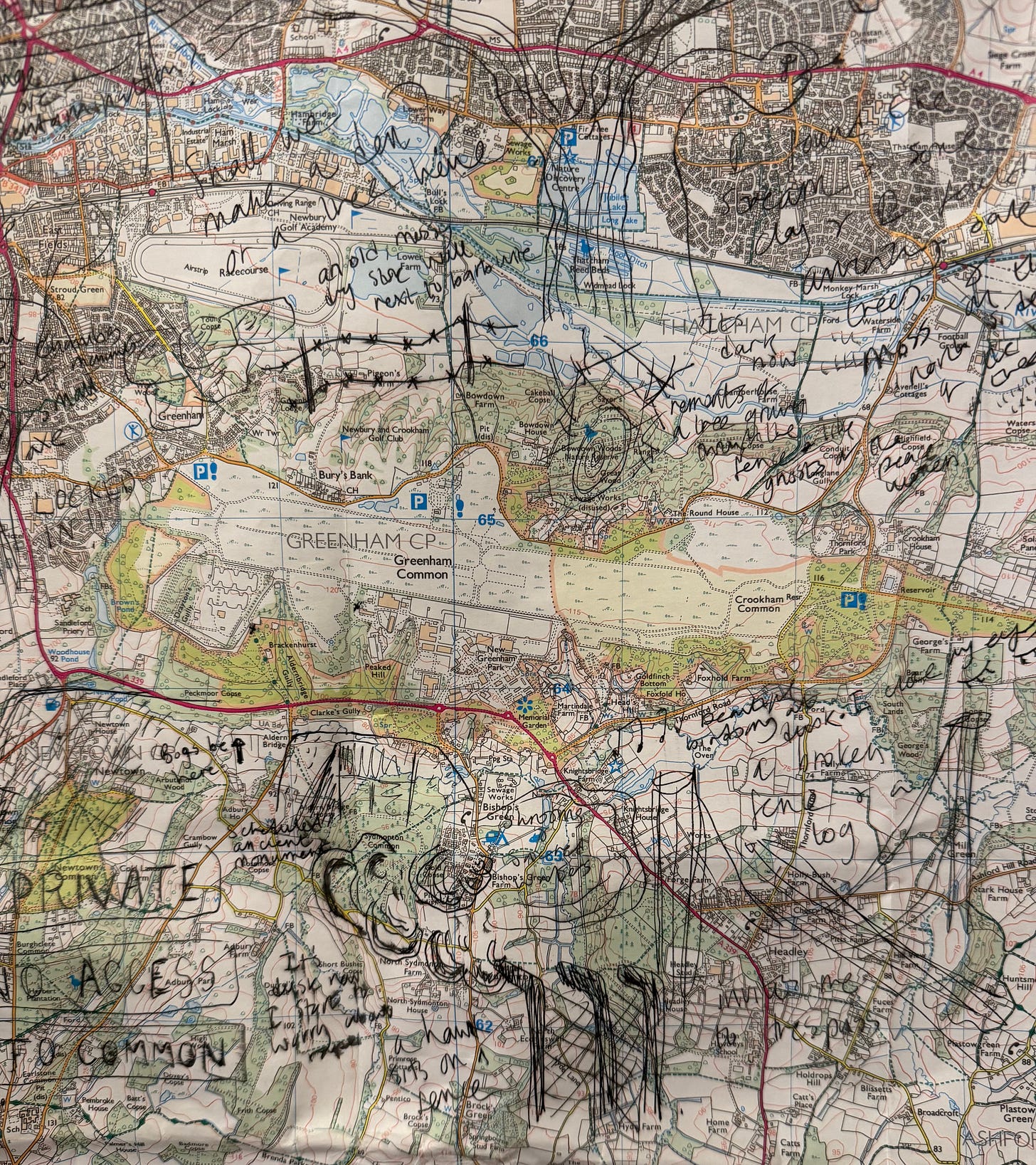

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Walking Without a Phone

We’re living in an age where walking without a phone – especially as a woman, and especially at night – is considered something of a radical act. But as I moved through the old runways and heathland of Greenham Common, I felt an unexpected sense of safety.

There was a presence with me – the echo of 70,000 women who once gathered here, holding vigil. I felt like I was walking with them.

In those moments, I found myself letting go of fear, shedding the instinct to be constantly alert or digitally tethered. What emerged instead was a different kind of instinct, one that trusts in vulnerability as strength.

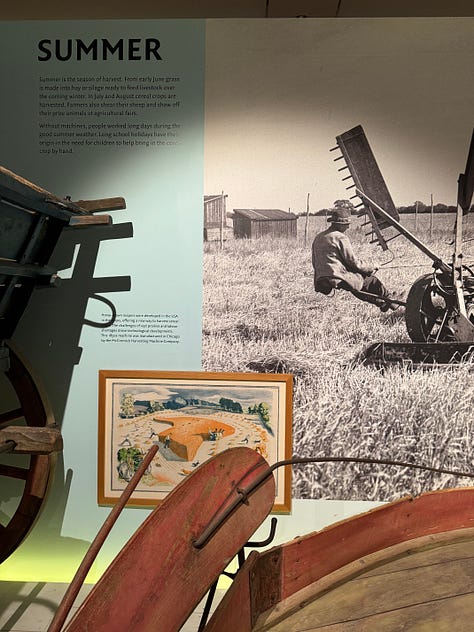

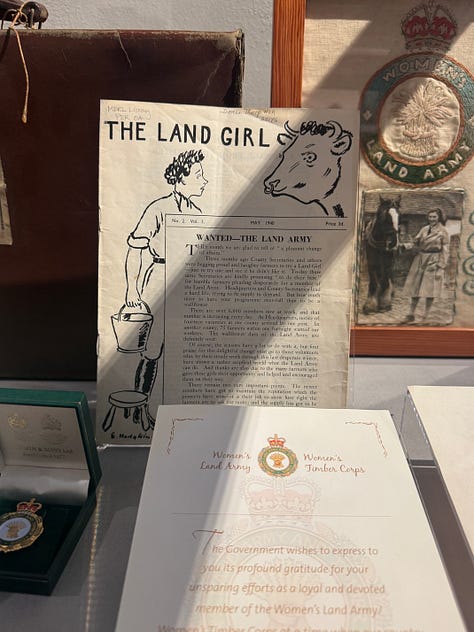

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Museum of English Rural Life

Interview with Dr Ollie Douglas, Curator of MERL Collections

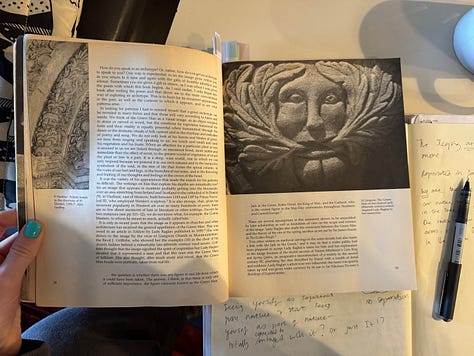

I visited the Museum of English Rural Life and met with Dr Ollie Douglas to explore the deeper resonances between land, class, folk culture, and the contemporary relevance of heritage. Our wide-ranging conversation gave me fresh insight into how the Green Woman might embody and respond to the shifting relationship between people, place, and protest.

Access, responsibility and rural identity

We began by unpacking what ‘access’ really means in the British countryside. Access to land isn’t neutral - it intersects with class, wealth, race, and historical exclusion. In capitalist society, land is something owned, not something you belong to. We talked about the rural working class and how rural heritage often fails to represent the reality of rural life.

Heritage as a living conversation

A key theme was the need to approach heritage with a critical and contemporary lens. As Ollie put it, “There’s little point preserving heritage if it’s disconnected from current discourse”. The Green Woman can act as a bridge between the past and the present - a symbol not of nostalgia, but of reimagination. We also talked about how artists can reanimate objects in museum collections, reinterpreting material culture in ways that are relevant, plural and political.

What do we mean by 'folk'?

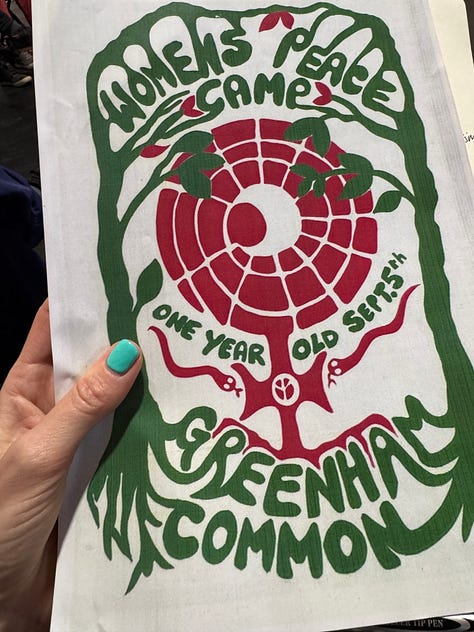

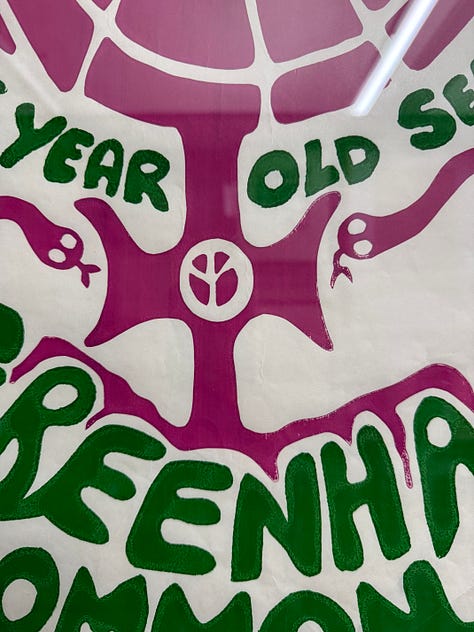

We explored the slipperiness of the term ‘folk’. It shifts meaning constantly - sometimes used to describe vernacular craft and grassroots culture, other times filtered through a colonial lens, or co-opted into a nationalist narrative. We shared an unease with the term 'outsider art' and a belief that much of what we consider 'folk' should reflect lived, collective experience. One of MERL’s original Greenham Common Peace Camp posters stood out to me as a powerful example of folk art - handmade, protest-driven, communal. A perfect reminder that folklore and activism are not separate spheres.

The Green Woman: myth, not romanticism

We spoke about the risk of over-romanticising folklore. It’s important to me that the Green Woman mythologises - but does not romanticise. This distinction is key: mythologising allows for symbolic, intuitive storytelling that still holds political weight and tension. Romanticism often erases or sanitises. The Green Woman must hold both beauty and grit, tenderness and resistance.

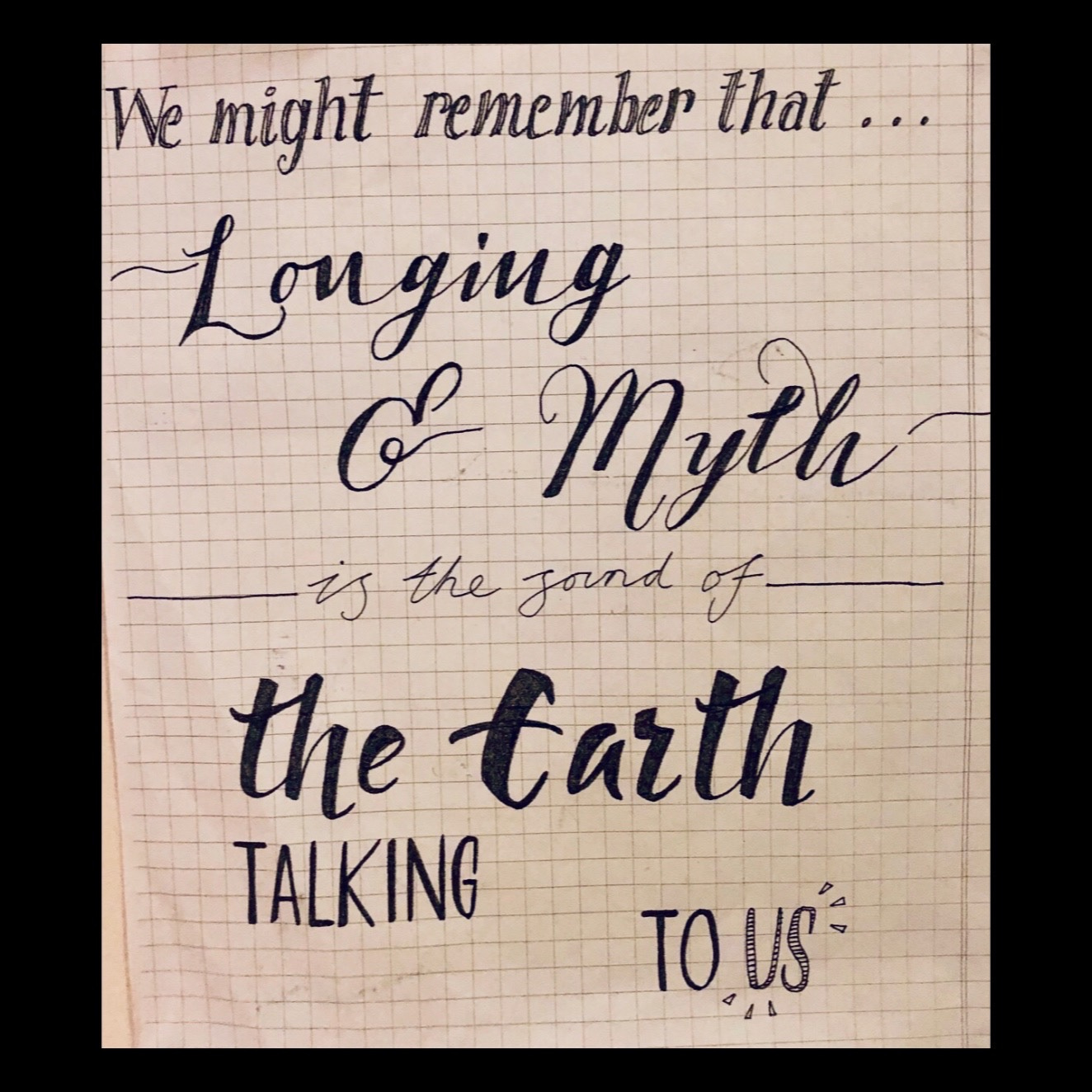

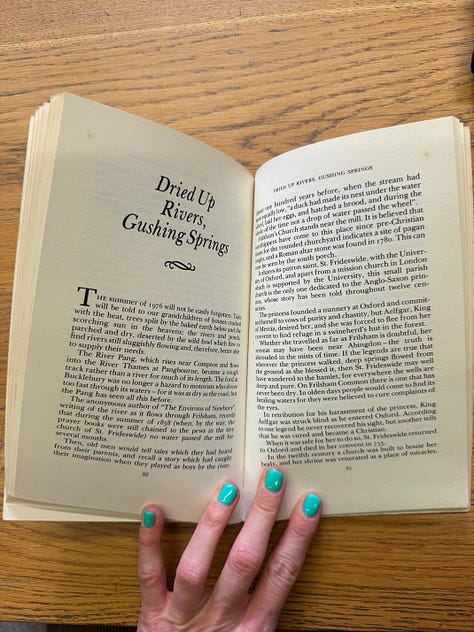

Cyclical time and climate memory

We explored how the Green Woman connects not only to seasonal cycles but also to much longer ecological and cultural cycles. Our climate memory is shaped by moments - Ollie suggested I look into the winter of 1947, the heatwave of 1976, and the Great Storm of 1987. These are markers in the collective memory of both human and more-than-human life. I left with a strong desire to speak directly with local commoners and farmers about how they experienced such events - and how those ancestral experiences shaped their connection to land, weather, and one another.

Commoning, ritual and fallow-time creativity

We also spoke about regional land-based customs - Plough Monday, strawcraft, mumming, grazing rituals - and how creativity and ritual often emerged during fallow times in the agricultural calendar. The working year was so physically demanding that these moments of performance and celebration were rare, but powerful. This idea links closely with my New Forest residency, where I explored land, and ritualised, seasonal creativity.

Gatekeeping, gender bias and the problem of singular narratives

We touched on how both museums and folk culture often reflect patriarchal, classist structures - with certain individuals acting as self-appointed ‘gatekeepers’. Folklore is rarely neutral. Whose gaze is it told through? Whose stories get excluded? I was reminded of the disempowerment of women and working-class communities in many dominant rural narratives. The Green Woman must resist this - embodying not a singular identity, but a plural, shifting voice. She must echo the collective, not the individual.

Resistance, resonance and the digital now

We ended with a reflection on cultural relevance. MERL’s ‘Absolute Unit’ tweet - the first museum object to be formally ‘collected’ as a meme - shows how digital culture intersects with heritage. If the Green Woman is a contemporary folk figure, what digital form might she take? Would she be a meme, a TikTok filter, or a video game shapeshifter? Could she hack pop culture from the inside out, as a Drag Race contestant, or K-pop artist? One thing is clear: she cannot be silenced. Like the Greenham Women, she must find ways to speak loudly, creatively, and inclusively - and be heard.

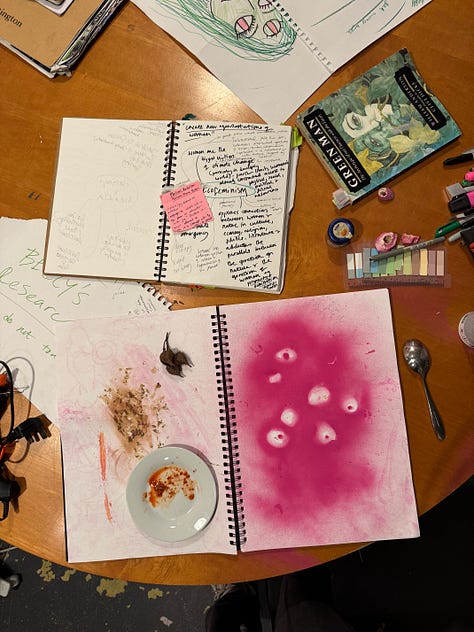

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Walking With My Camera + Experiments

Walk and Talk with Julian Cooper; Land Manager, BBOWT, Greenham Common

I met Julian for a walking conversation across Greenham Common – a place that, for him, holds an intricate weave of natural history, military legacy, community potential and ecological futures. As Land Manager for BBOWT, Julian is deeply invested in the interplay between humans and the more-than-human world – not as separate entities, but as one evolving, interdependent system. I was joined on the walk by fellow Seedbed artist, Hamshya.

A living, layered landscape

Julian described Greenham as a “layered natural and cultural history” – a post-apocalyptic-feeling site where wildness is reclaiming industrialised space, and where culture and ecology are not in opposition but in conversation. For him, the vision is one of “culture-building”: a future in which nature conservation, community engagement, public ownership and shared responsibility are intertwined.

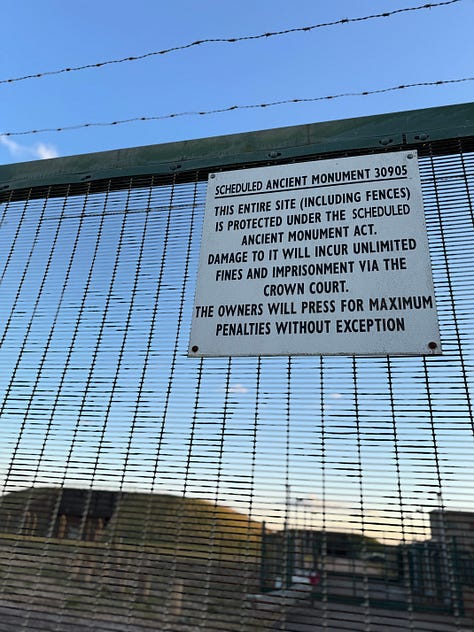

He imagines a time 50 years from now when lapwings, nightjars, adders, dartford warblers, gentians and wildflowers are thriving across the Common. Gorse, he noted, will always be part of the story – ancient, enduring, essential. The old military fencing? He hopes it stays too – a weathered monument to difficult histories, raising important questions about war, peace, and human intervention.

In 500 years, Julian imagines the tarmac will be long gone, erased by time and weather, but the Common will remain – still managed for biodiversity he hopes, still holding traces of its cultural memory, and still alive with wildness.

Slowness, stewardship, and shared responsibility

“What’s the rush?” he asked, with gentle irony – acknowledging both the urgency of the climate emergency and the need for long-term thinking. Sustainable landscapes take time. He spoke of thinking in the lifetimes of oak and stone – and of management practices that must evolve alongside the land itself, rather than trying to control or contain it.

This is a working landscape – not a museum or a postcard. Human intervention can be both destructive and regenerative. He pointed to the decline in ground-nesting birds due to irresponsible dog walkers – but also their recent resurgence thanks to ranger-led conservation efforts. Stewardship, not extraction, is the ethos Julian holds to. He spoke about the need for collective responsibility – not just the claiming of rights, but the honouring of responsibilities that come with them.

The common and the cultural

We spoke about the idea of the ‘common’ – a space shaped by shared access, use, care. Julian is passionate about instilling a sense of local ownership of the site – not bureaucratic ownership, but belonging. “Our common,” he called it. Access, we discussed, means different things depending on your background: poverty, race, gender all affect how welcome and safe a person might feel in a landscape - echoing my discussion with Ollie, at MERL. These questions also mirrored concerns I explored in my New Forest residency.

We spoke about public ritual and community engagement – the possibilities of reintroducing collective acts of land care and creativity. While fires aren’t permitted on the common, Julian spoke about the controlled burning of gorse, and fellow Seedbed artist, Hamshya, and myself wondered: could this become a symbolic public ritual? A gathering around managed fire – not destruction, but seasonal renewal? perhaps the seeding of a future collaboration…

Margins, ecotones and radical growth

We discussed the concept of ecotones – transitional edges between habitats, often the most biodiverse places in the landscape. This resonates deeply with me. I saw a metaphor forming – between ecotones and the Greenham Peace Camp. The margins are where the most radical things happen – and often, the most conflict.

I asked, “Isn’t culture just another expression of nature?” Julian agreed. This site, for him, is a space where those blurred edges meet. Where culture and ecology, memory and protest, species and symbols coexist. The Green Woman belongs here – as much as the reptiles and wildflowers.

From enclosures to collective futures

Julian spoke about the long legacy of the Enclosures Act, and the impact of post-WWII land changes on our sense of ownership and access. We agreed that we need more connectivity – both ecological (more corridors, more openness to desire paths) and cultural. Management practices, too, must catch up with the changing landscape – evolving at the same rate the land is evolving.

Finally we discussed the ancient history of the site - the burial mounds (which he hopes to source a map of) and a neolithic axe found on the site, along with other

He left me with a powerful suggestion: the possibility of using the space between the twin fences in front of the missile shelters – a symbolic site of separation and control, now ripe with potential for new stories. There’s something potent in that threshold space – between what was, and what could be.

Visual Diary: Residency Week - Early Tests

Visual Diary: Post Residency Week - Test Shoot in Hastings

“It’s nice to be a child, but we have to grow up.” Uni.

Future Myth Text

🌿 The Weaving of the Green Women 🌿

(A fragment of an ancient telling, gathered from glyphs on relic-fenceposts and the chants of the Wildland Wanderers of the South Common. Origin: Lost, Circa 5000 CE.)

1. The Age of Iron and Ash

Long before the forests returned, before the rivers carved new paths through the ruins, there was a time of great forgetting. The land was bound in wire and stone, its lifelines severed. The sky burned with the fire of war-gods, and the people were made to believe they were separate from the earth beneath them. But the earth remembers. Beneath the fences, beneath the roads, beneath the weight of empire, there had always been threads.

~

Five great burial mounds once rose from the Common, their soft, ancient, earthen shapes cradling the souls of those who came before. But the warlords did not see them. They cut through the landscape, shattered the stones, and buried the bones beneath concrete and steel domes.

And yet, unknowingly, they built their domes of destruction in the image of the ancient mounds. The very ones they had destroyed. Vaults of reinforced concrete, ribbed like the back of a sleeping beast. A pattern, repeating. The threads, unbroken.

And so, the land called forth its weavers.

It is said that in those days, a gathering of women came from all corners of the earth to the edge of destruction. They were not warriors, and yet they fought. They carried no blades, yet they cut through the iron chains of empire. At their peak, they numbered seventy thousand - daughters, mothers, grandmothers, women born female or otherwise, and girls still too young to braid their own hair.

They called themselves the Green Women, and they wove the first unbreakable wild web.

And through them, something ancient stirred - the memory of renewal, the cyclical pulse of land returned to itself.

2. The Weaving of the Wild Web

The Green Women did not march as armies did. They did not build as the old rulers built. They wove.

With hands calloused from work, they spun threads of many colours, knotting them into fences of steel, binding war machines in a fierce softness that could not be severed. They wove with wool, and with wire stripped from the warlords’ own defences.

They cut through the fences in the night, slipping into the forbidden lands. They walked defiantly where none were meant to walk. They danced upon the domes of destruction, their feet striking rhythms against the war-machine vaults, their voices rising into the wind. Some say the earth itself shook with joy.

Some say it was the rhythm of threads and roots waking beneath them.

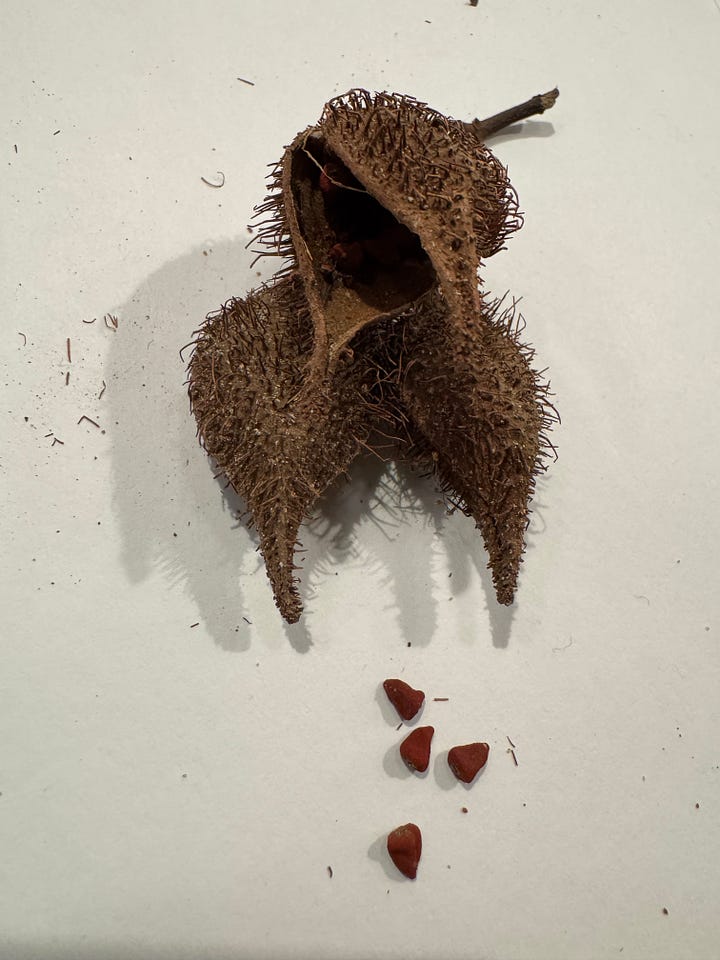

They foraged wild clay from the sacred streams, shaping small, earthen Green Women, each one marked with the thumbprint of its maker. Some they kept as talismans, fired in their hearths, and some they buried in the gravelly, forbidden ground, pressing them into the warlords’ land like seeds in the weave of the earth.

And like seeds, they waited.

They found a stone axe, deep in the gravel. A tool of ancient hands - now bones under domes - smoothed by time. They held it, knowing they were not the first, and would not be the last, to shape the world with their work. Some say they used it to carve new lines in the land, to remind the warlords that no thread can be truly severed. Others say they simply held it, letting its weight sink into their palms, feeling the pull of the past within them.

Their wild weaving was more than cloth - it was a network, a map, a spell. With each knot, they whispered the names of spores, of seeds, of daughters not yet born. Wearing hag stone necklaces for second sight, they drank the gorse flower remedy, golden and spiked with sunlight, so that their voices would stay strong, and their bodies unbroken.

They marked time not in hours, but in cycles - in bloom and decay, in root and rise.

At night, the Green Women lit fires - not for war, but for warmth. Their green flames curled over blackened cauldrons, sending pink smoke twisting into the sky. And when the wind shifted through the fences, it carried their voices beyond the walls, beyond time.

And then - on the longest night, beneath the watching stars - thousands of Green Women joined hands and encircled the warlords’ stronghold. They wove their bodies into a living web, a ring unbroken, a binding spell of flesh and will.

The warlords mocked them at first, called their threads fragile things. But when they sent their iron-clad men to tear the web apart, the soldiers found themselves ensnared - not in thread, but in memory.

For the wild Green Women did not weave alone. The land wove with them. The trees, the wind, the fungus, the roots of forgotten things - they all rose in answer.

And in time, the warlords fell.

Their empire unravelled, thread by thread.

The land was returned to itself.

The wild web held.

And each year, when spring came, it came greener than before.

3. The Giant of the Commonlands

Nowadays, there are those who say that if you walk the old paths at dusk, you might see her -

The last Green Woman, taller than trees,

her skin a tapestry of ivy and rusted wire,

her fingers dripping with thread,

her hair tangled with the banners of those who came before,

and vines spilling from her mouth - tendrils of blossom, bud, and leaf, as though the earth itself is speaking through her.

Some claim the Green Women were never real, only a vision, a story shaped by wind and want. But the Wildland Wanderers of the South-Common say that the last of the Green Women still walks, her giant footsteps pressing into the softened earth, reminding the land that it was never meant for war.

They see that the proof is there.

In the trees that grew through the iron.

In the vines that wove themselves around fences.

In the adders who still thread through the gorse.

In the nightjars who churr in the dusk, their silent wings brushing the air where the web once was.

In the fire-lit figures of clay, placed at the roots of ancient trees.

In the hands that still weave, still bind, still remember.

And when, wrapped in embroidered blankets stitched with Wildland sigils, the Wanderers return to the mounds -

To the soft hills where the five great barrows once rose,

where the domes of destruction still curve beneath the bracken, rusting quietly into earth -

they form circles under the stars and search for hag stones.

They press their thumbs into fresh clay, whisper old chants into the soil,

tie yarn to the fencebones that still rise from the land like relics.

They light green fires and sip the gorse-flower remedy,

feeling the fire stir in their bellies.

The Green Woman is not a ghost.

She is not a memory or a monument.

She is the web.

She is the land.

She is what happens when hands join together.

She is what happens when we refuse to be unthreaded.

She rises again - returning in cycles, not in conquest. In bloom, not in battle.

In every act of wild remembering, each time we dare to weave.

To Be Continued…