INTUITION MAPS visual essay, research and process by Beccy Mccray

Commissioned by Fermynwoods Contemporary Art, with thanks to Northamptonshire Community Foundation’s Creative Climate Action Fund.

PROLOGUE

As I write this prologue on the 5th of August 2024, in the midst of right wing race riots in the UK, it strikes me that the current political landscape has brought this artwork to a different place.

I realise that I had fallen into the trap of oversimplifying to prove my own point. Through my process documented below, I now further acknowledge the complex human problems which the more-than-human world do not face, as well as my own privilege, and the heightened relevance of this artwork.

We urgently need new narratives around migration. Stories of active hope, solidarity and connection, stories that break down the harmful narrative of separation, and stories which oppose disinformation, far right rhetoric and the capitalist agenda.

Read on as I take you through my process, research and thoughts leading up to the final intervention artwork.

INTRO

My practice sits at the intersection of art and activism, philosophy and politics, science and spirituality. I'm excited by process and research, often teaming up with scientists and other experts. My work increasingly explores the British landscape in relation to my interdisciplinary interests and questions around ecology and folklore. As an artist, my practice is the methodology for tackling these interests – my reading, thinking, writing, making is an approach to my research, which deals in the visual as well as the theoretical.

SEEDING NEW NARRATIVES

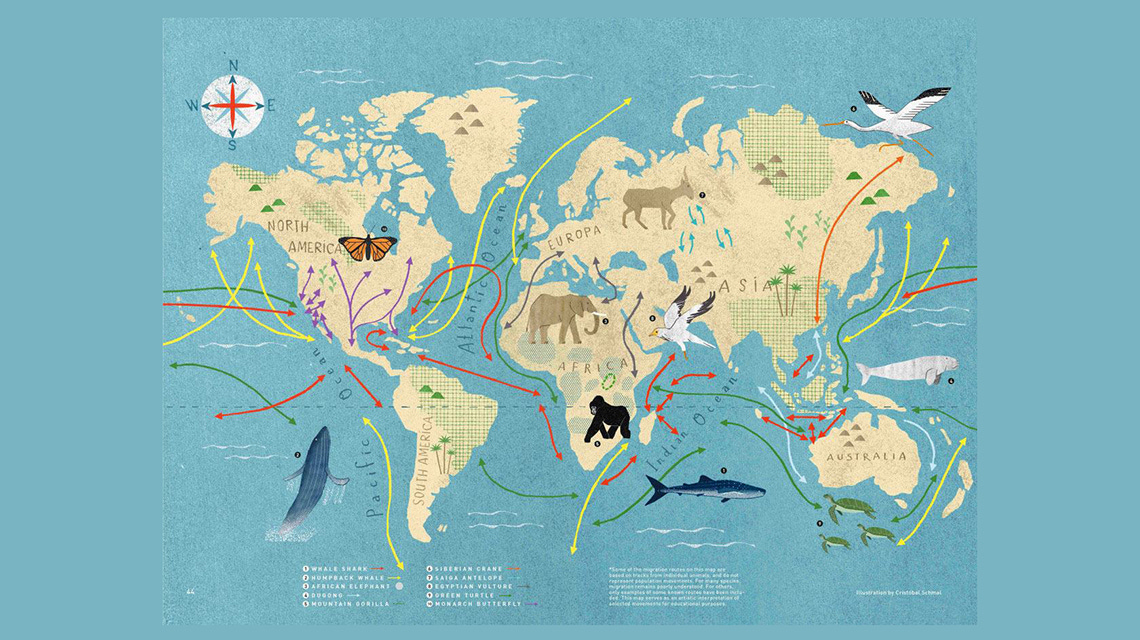

We look at the more-than-human world and believe that we are separate from it. We comment on ‘animal instincts’, excluding our own behaviour and intuition from this. We marvel at murmurations and celebrate stories of birds and insects that travel thousands of miles to land on our shores from far away countries whose conditions are no longer life-serving - whilst at the same time demonising those humans (many from the global South migrating to the North) who’re forced to flee from lands ravaged by floods, fires and famine (much of which caused by the global North’s CO2 emissions), as well as civil unrest, persecution and war.

The current dominant narratives tell us we are separate from nature. Because we think like this, we are literally changing the geology of our earth, causing mass extinction, and becoming more and more disconnected from each other. By believing that we’re separate from nature, we don’t see this as a problem.

But we are wrong. We are a part of nature. In fact, we ARE nature. We are completely interconnected with all life on this earth.

Intuition Maps responds to this idea, addressing intersectional environmentalism: the legacies of colonialism and capitalism, climate justice, racial justice, land justice, rights of nature and the human rights of people to move and seek safety. It observes the instinctive mass movement of people and animals, seeking to draw comparisons between the two, building empathy, solidarity and hope, generating a sense of connectedness to each other and the more-than-human world.

Join me for a guided walk at the launch event on September 15th, 2024: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/intuition-maps-beccy-mccray-tickets-991060527717?aff=erelexpmlt

PROCESS AND SEARCHING FOR PATTERNS

Intuition Maps is a co-created artwork which invites participants and visitors to reflect on animal instincts - that of the more-than-human world and their own - in the context of climate change adaptation.

My guiding principles for the process were:

Convene. Participate. Play. Agency. Action. Non-extractive.

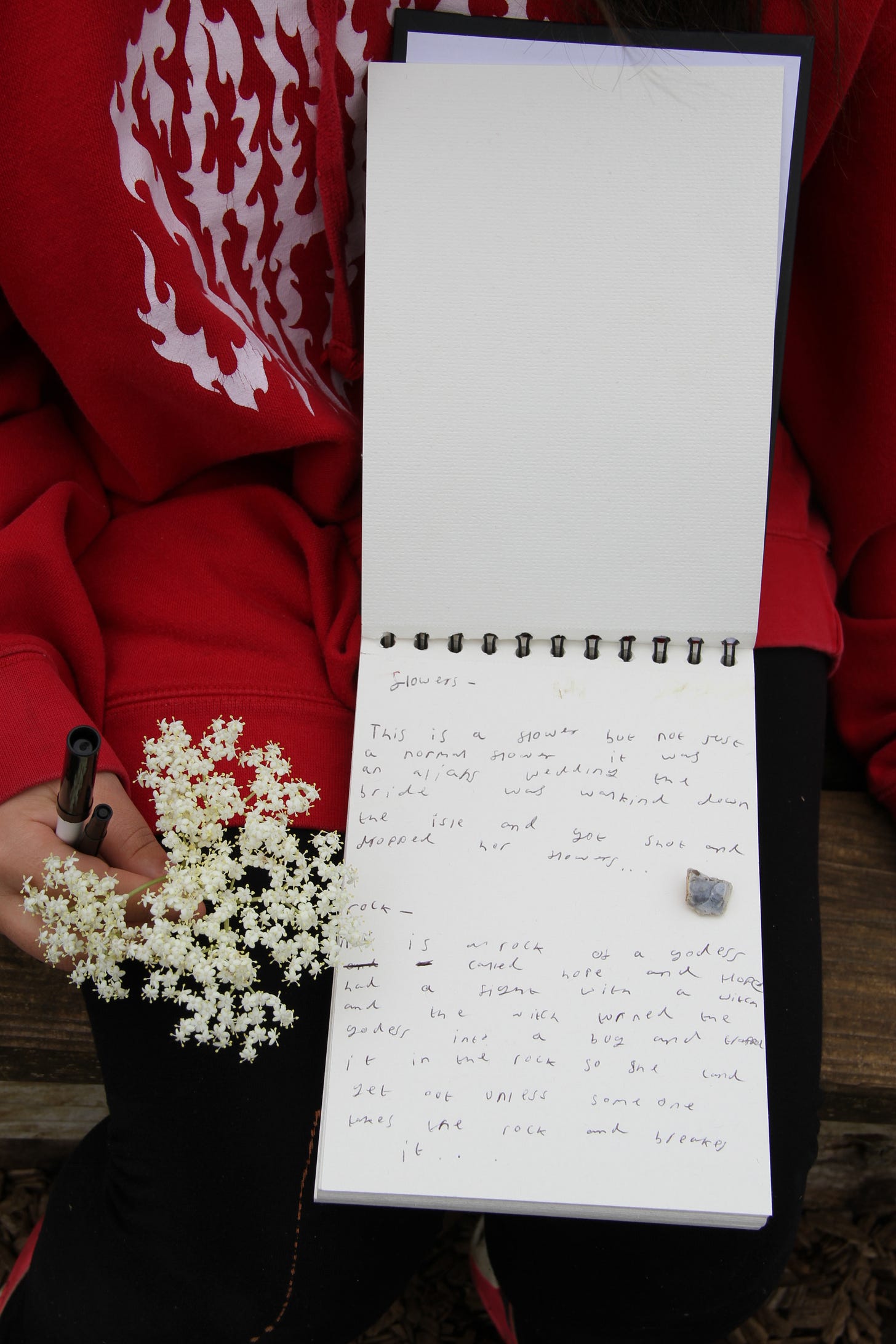

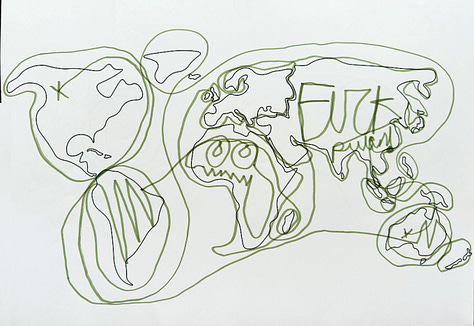

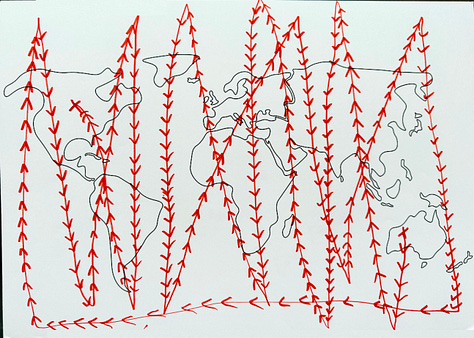

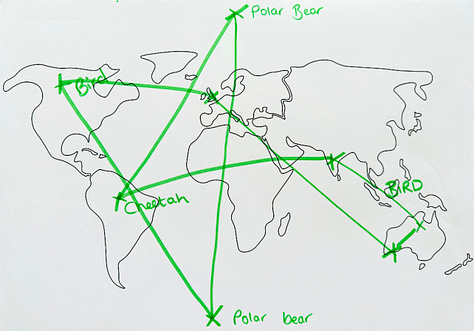

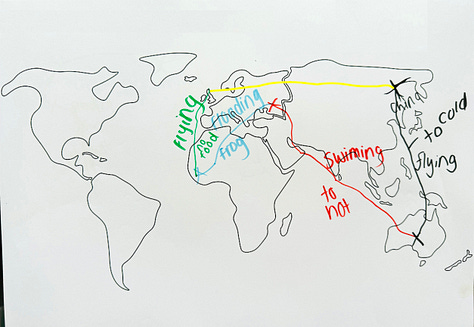

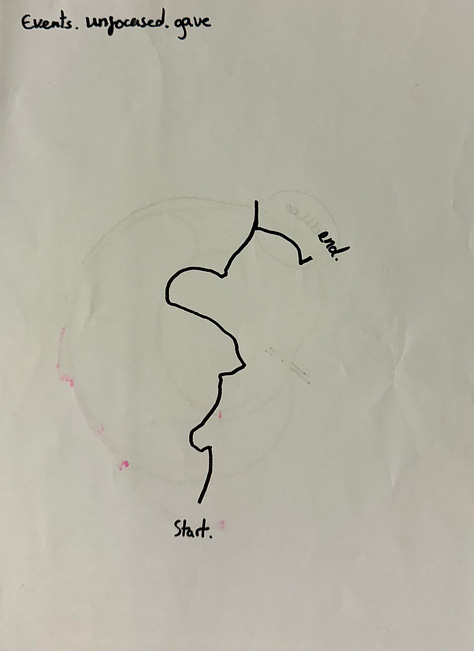

In embodied, ecosomatic workshops with Northamptonshire communities we explored our own instincts, whilst documenting sensory and emotional perceptions. We used nature connection exercises and floor-sized atlases, responding to speculative global climate scenarios like extreme heat and cold, rising sea levels and food security issues, demonstrating ways that we might move and routes that we might take.

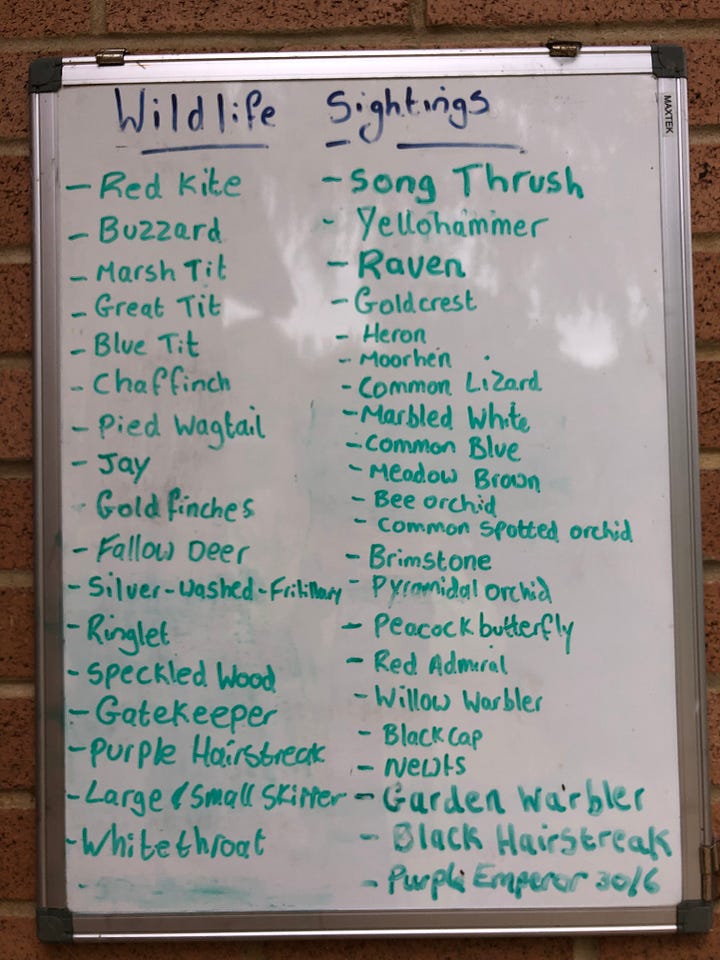

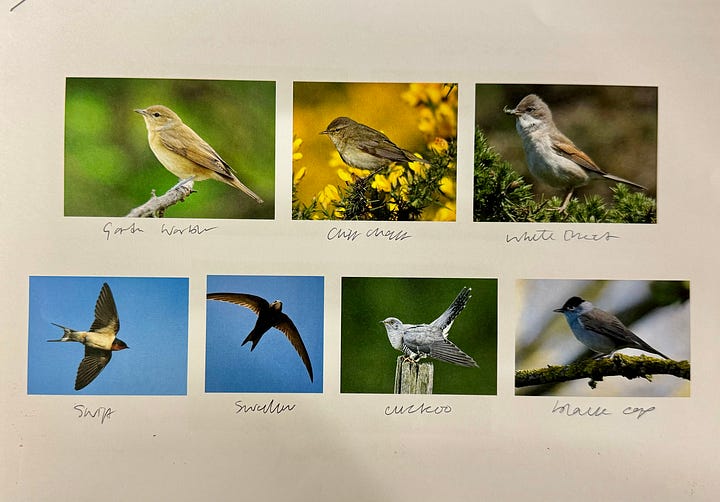

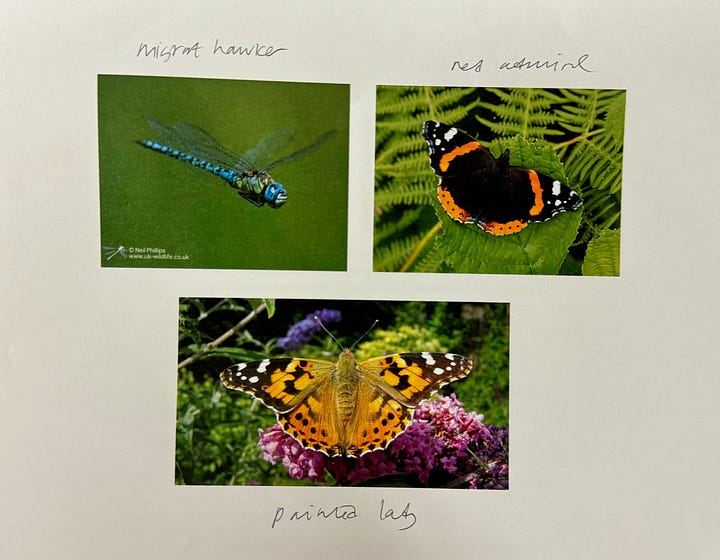

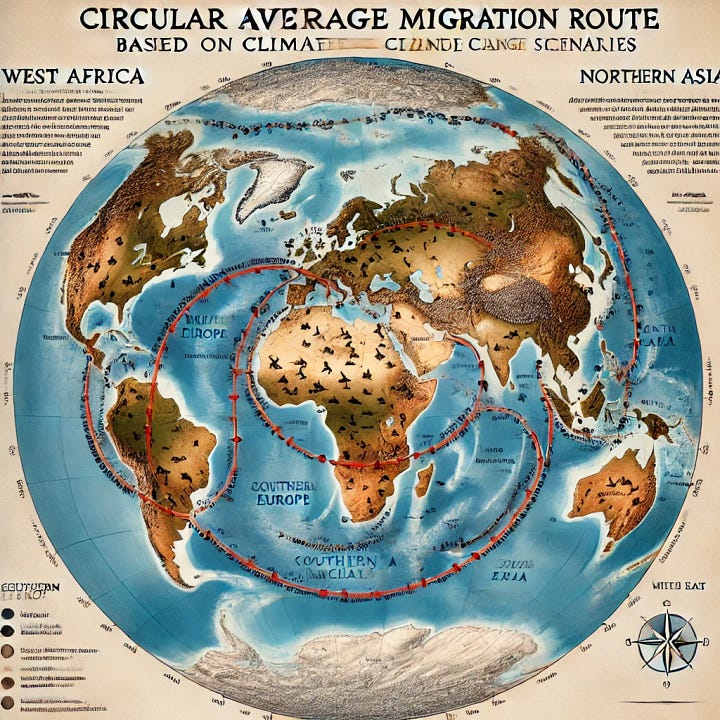

Through this collaboration with local communities, plus wildlife experts, local migratory species (specifically working with the migration routes of garden warblers, chiff chaffs, white throats, swifts, swallows, cuckoos, black caps, migrant hawker dragon flies, red admiral & painted lady butterflies) alongside a custom AI algorithm I was able to combine data - the idea being that the machine learnt from nature rather than about. The AI was able to analyse the data and map speculative future movement, seeking out patterns and generating, or predicting, a new, collective route - revealing that we’re not so different to migratory birds and insects – or each other.

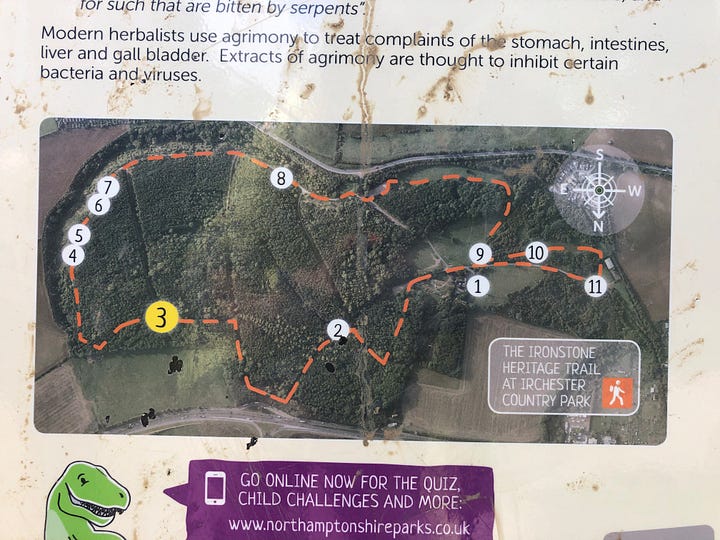

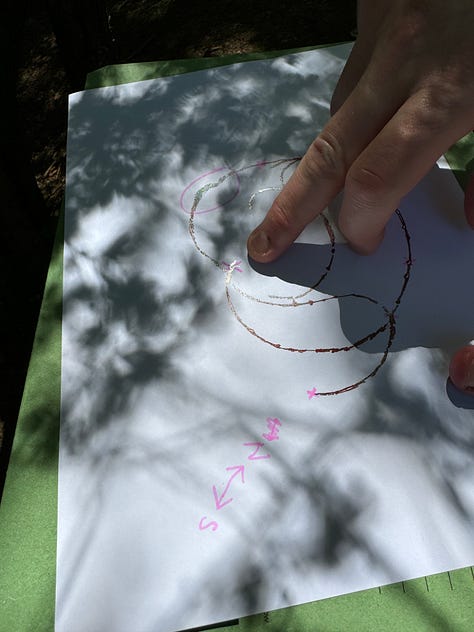

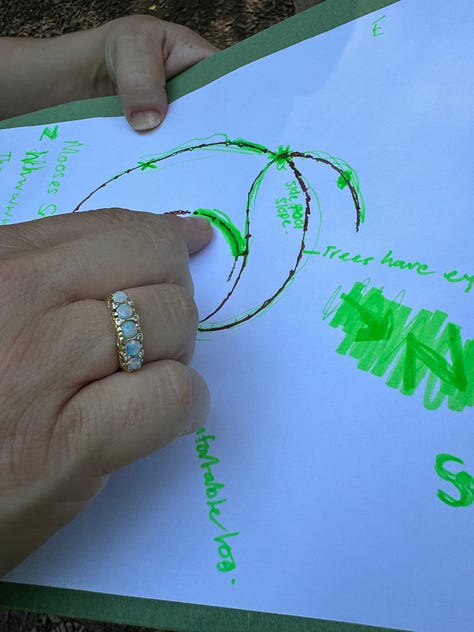

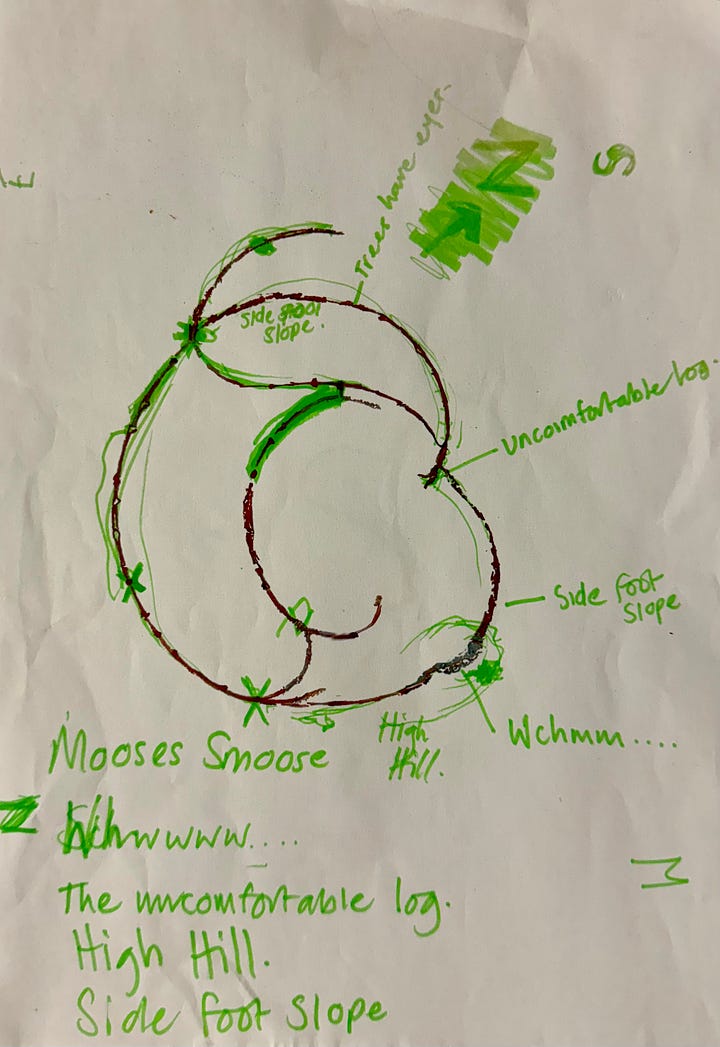

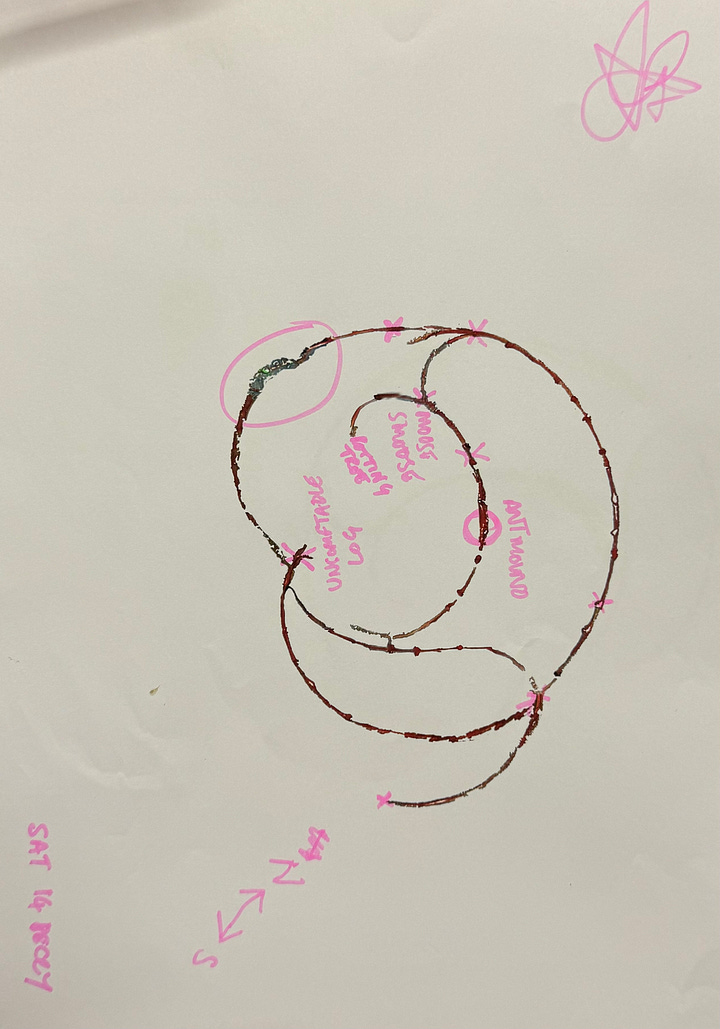

Participants were later invited to an experimental ‘walkshop’, where they could have their say in the final intervention artwork. In this sensorial, walking workshop in the woods we zoomed in from macrocosm to microcosm (or global to hyper-local), interpreting the AI-generated pattern to navigate a new and unexpected walking route, and deciding where to place waymark interventions.

I asked participants to put their phones away and interpret the patterns using only their embodied intelligence; reading the landscape, listening, looking at the light, the position of the sun and tracking environmental conditions like wind direction. To tune into their senses and animal instincts – in a sense, rewilding themselves.

I encouraged participants to use the rides and firebreaks, smoots and smeuses, stray from the beaten path and use the existing ones as little as possible. Desire paths and emergent behaviour were welcomed.

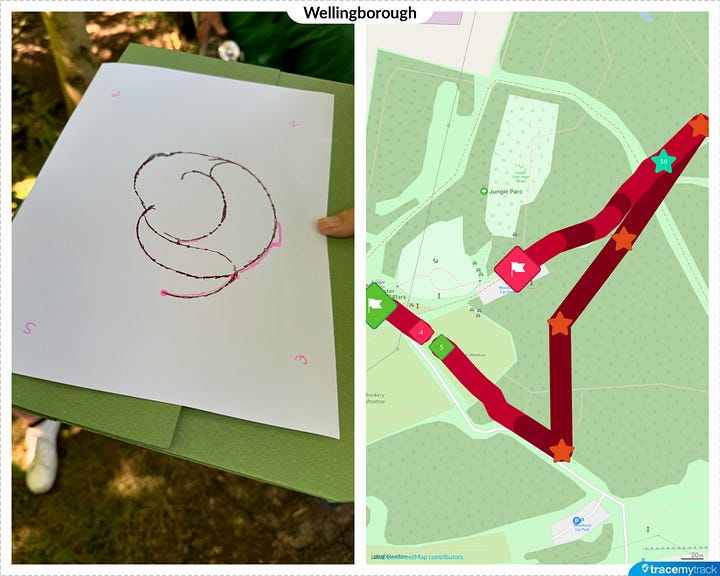

My role as the Artist was to simply observe and document the new route to aid the installation process (using the apps Trace My Walk, What 3 Words, and Google Earth creation tools). We decentralised and self organised – the participants lead the expedition themselves and forged a path together. I wanted to notice what unplanned things were happening within the group - what was working/wasn’t working? Would they cooperate and function as a collective – or act as individual agents? What relationships would be formed within it? Could we operate like fractals?

The group split in two - the young people and the adults. The young people disappeared with the GoPro, relying entirely on their own instinctual exploration of the woods - and left the adults to carry out the more formal experiment.

And yet, interestingly, we continued to cross paths. The wide-ranging circular route the groups imagined they’d taken was in fact a much more linear trail, pushing less than halfway into the total area of the woods, but still very much off the beaten track.

The core human participants involved in the project were teenagers excluded from mainstream education – it’s interesting to reflect on how these mostly postcode-bound young people with firm roots in the area have influenced the artwork. Learning about their values, hopes and fears, and embracing their instinctive, uncontrived and unpredictable participation has certainly affected the course of the project – in the words of David Graeber they act like they are already free. Perhaps something the rest of us can learn from.

Working with unpredictable levels of participation gave the project an emergent property. I had to let it evolve and take shape in its own time; building, dismantling and re-building at different stages of the process.

This idea of constantly building on previous patterns runs through the core of this artwork, and is something I reflect on a lot. Things that can be seen as destructive are often a force of creation.

The land at Irchester itself bears the scars of previous patterns; its pits, ponds, furrows, ditches, ridges, hill and vale tell of the area’s previous embodiment as an ironstone mine. After mining was stopped the Forestry Commission mono-cropped a commercial plantation, and more recently the Woodland Trust are trying to restore more locally appropriate tree species. Each of these interventions however builds on previous patterns and creates new habitats - the foxes, badgers, muntjack deer, and butterflies all thrive in the relatively newly created vale (the ditches and scrub). This, like all landscapes, and the pattern-building process behind Intuition Maps, is constantly evolving.

As I write, the final waymarks are being fabricated, ready for installation at Irchester Country Park woods, with a special opening event on Sept 15th which all participants and the general public are welcomed to join.

MIGRATION IS A SOLUTION NOT A PROBLEM

Swifts, cuckoos, wildebeest and basking sharks – we admire these creatures for their epic seasonal migrations. But there is another, far bigger group of species who undertake even more audacious journeys: insects.

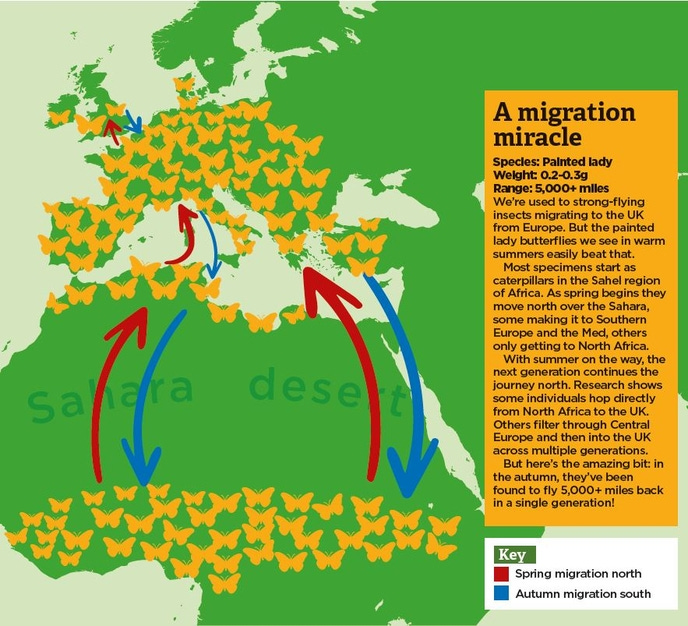

The Painted Lady is Britain’s best-known migratory insect but there are many others, including moths, dragonflies, ladybirds, hoverflies and even aphids. Climate change will bring yet more to our shores. It seems far-fetched that insects can cross continents, but we now know they do.

Migratory drivers for most species are temperature, food source and breeding possibilities. For British butterflies this is no different, the big challenge is to survive winters when caterpillars’ food plants don’t grow. Most do this by hibernating, but migrants such as the Painted Lady survive by moving south, to warmer climes.

It was long assumed that the Painted Lady retreated to Morocco, but scientists recently discovered that it also crosses the Sahara, then, when it gets too hot for the sub-Saharan African generation, they move north again. The Painted Lady migration route can span up to 7,500 miles, and this can be via three or more quickly-reproducing generations. Rising at an average of 500 metres they take advantage of prevailing winds, flying at an unbelievable 30mph.

But how do these insects know which way to go? Lab tests have revealed that the lengthening or shortening of days is the Painted Ladies’ cue: caterpillars growing while days lengthen become adults who fly northwards. When days shorten, the butterflies are born with an awareness of the need to travel south, to warmer climes. The Painted Lady then orientates itself using the sun, although studies have revealed that other aerial migratory species use the Earth’s magnetic field, or a mental compass, to guide them. All species rely on reading the weather and tracking environmental conditions, but other suggestions include the use of constellations, sense of smell, following mentors, and following visual landmarks including roads – but in truth, there is still so much we don’t yet know about this mysterious form of encoded, embodied intelligence.

It’s not just their miraculous journeys which make migratory species so special – they are important to our ecosystems too – and of course, like all living creatures, their existence does not need to be justified.

As the climate changes – and this doesn’t just mean temperature, but other factors such as prevailing winds - some dispersing insects will take up permanent residence in Britain. In fact, the migratory Red Admiral butterfly, a common visitor to Northamptonshire, has already been recorded hibernating here, taking advantage of the milder winters. But as some species will benefit from the changing climate, others will suffer.

Phenology – the branch of ecology that studies the seasonal and cyclical nature of natural phenomena and life cycle events, especially in relation to climate/plant/animal life (e.g. migratory patterns, timings, behaviour, availability of food, nesting, feeding etc) is teaching us that creatures can’t evolve at the current pace of human-induced climate change. This has a much larger impact on migratory species because they require multiple habitats. In line with this research, rangers at Irchester Country Park have documented many migratory species arriving two weeks earlier in the season. The implication of this is that that life cycles up and down the chain become out of sync – which can lead to potentially catastrophic effects, from pests and disease, to food shortages and sometimes extinction.

How different species – including humans - respond to climate change is key to whether populations will persist or go extinct. One in five migratory species are threatened with extinction and nearly half show population decline. For some it’s even worse. Turtle Dove numbers in the UK have plummeted by an estimated 99% since their peak in the late 1960s. Research has shown that a loss of breeding season habitats that provide seed food for the doves was the single most important factor in their decline. We’re a nation of bird lovers, and yet our population is one of the most rapidly declining in the world.

To help populations recover we must establish key biodiversity sites on migratory pathways, reduce blocking infrastructure (e.g. roads and dams), create wildlife corridors to protect habitats and boost connectivity, and we must stay below the 1.5C threshold.

Most of us love our swallows, our swifts, our cuckoos – ‘our birds’ - and would encourage anything that improved their chances of survival. ‘Our birds’ spend ten months of their year in Africa - and yet we willingly adopt them as our own, welcoming them acting on their instinct, making incredible and dangerous journeys to our shores in order to feed and nest and continue the survival of their species.

What if we applied some of this thinking to complex human problems too? What if instead of creating ‘hostile environments’ and deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda we placed more cultural and spiritual value on our immigrant populations, and celebrated their place within human ecosystems, boosting connectivity, reducing blocks, and creating abundant, safe spaces and passageways for families to grow and thrive?

COMPLEX HUMAN PROBLEMS

Birds are used as warning indicators of environmental change - the changes we now observe in their migration patterns reflect significant climate and habitat changes. The flightways of birds have also become the routes of flight for some refugees. But why do people take these more dangerous, illegal routes, and why are they demonised for doing so?

Interestingly, studies have shown that some starlings no longer migrate when their flock becomes large enough to generate enough warmth to see themselves through the winter. And similarly, rewilding pioneers at at Knepp have noted that the storks there lose their migratory instinct when fed through the winter.

We know that ancient humans before the advent of agriculture lead more nomadic, migratory lives, and that the farming of crops and livestock lead to a more rooted existence. Our human faculties are tied to nature and the seasons – but are our present day senses and instincts being flattened by a dependence on technology and urban environments? And could we make those same epic, migratory journeys today, without the use of modern technology?

Most humans don’t want to migrate if they don’t need to for safety or survival reasons – in all species resilience and adaptation generally results before migration. But unlike birds and insects, humans – specifically those seeking refuge or asylum - have to deal with intersectional drivers and barriers, and social and geopolitical constructs like racism, homophobia, misogyny, poverty, war, political clampdowns, borders and nationhood - as well as famine, drought, floods, climate change and other weather-related events.

IPCC predicts that by 2050 there may be as many as 1.2b climate migrants – this number includes ecological threats such as conflict and civil unrest - lower figures point to an estimated 50m. But who actually has the means to migrate? At risk, wealthy countries like Qatar have the resources to build defences, but the already marginalised, poor countries, like Bangladesh, are inevitably the most vulnerable.

Britain is not immune to this; some of my recent work has taught me that places along the East coast including Skegness, Doncaster, Hull and Ipswich are at severe risk of the impacts of rising sea levels, leading to devastating floods by 2050 regardless of any mitigation that may now be put in place to reduce global emissions. The damage has already been done – and indeed, some of the effects are already being experienced. Moving within one’s own country usually happens before crossing borders, or the South to North narrative. But how much does Whitehall care about the residents of a deprived area like Doncaster? Could you and I be climate refuges one day?

The words ‘climate change knows no borders and neither should we’ is sometimes used in environmental circles, but is this rhetoric and the term ‘climate refugee’ in itself problematic? Does it create yet more fear and coercive pressure? It’s an idea that can be easily twisted into an ecofascist, polarised polemic, pitching human rights against national security.

In a world where the global north sends it carbon footprint south, a world where developing countries contribute to just 10% of C02 emissions but foot 75% of the costs, and a world stuck in the legacy of colonialism and capitalism (enslave and extract then protect the spoils of empire and insulate from immigration) we desperately need climate justice, racial justice and the human right to move freely and seek safety.

One thing is certain; we need new narratives around migration – not lies and disinformation, racism, othering, fear-mongering, and all the other harmful narratives and distractions controlled by right wing media who have the means and resources to disseminate them. We need more stories motivated by love not fear, stories of mutual aid, fictive kinship and active hope. Cooperation over competition. Stories that redefine success as interdependence and solidarity.

Maybe art can help seed these new narratives, and create safe spaces to have these often difficult conversations.

INTUITION, DIVINATION & MACHINE LEARNING

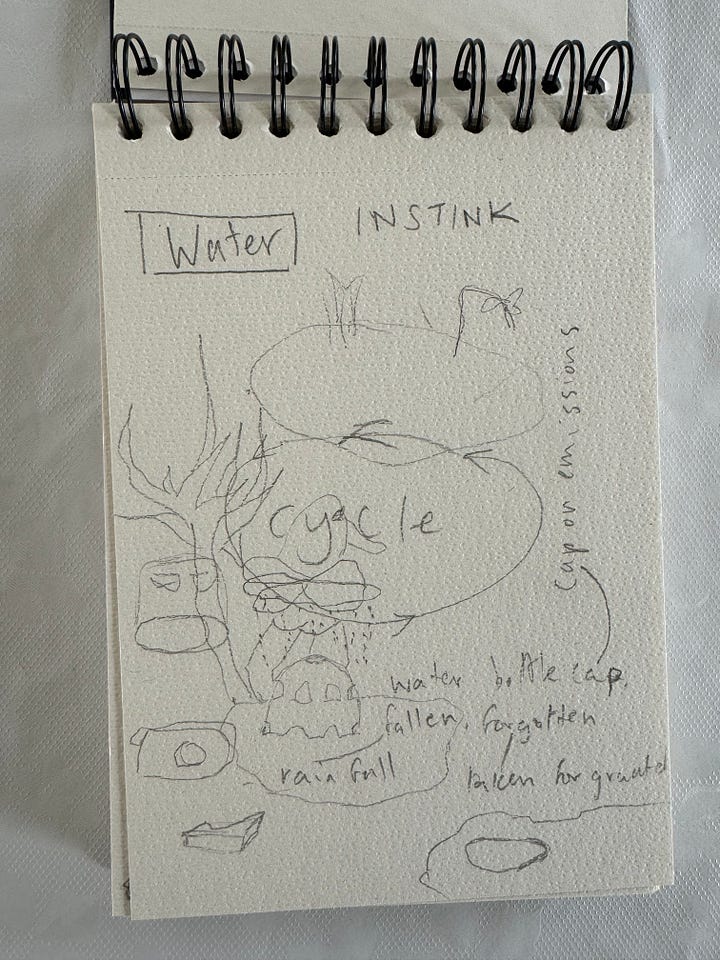

Increasingly I aim to work intuitively, exercising my gut instinct and engaging in occult rituals of practice to read signs, to search for patterns and guidance, and to tune into the will of the universe. Although I do not attempt to predict the future, the art of divination interests me and I feel that this relates to my Romany heritage.

AI intrigues me, it has the potential for both great destruction and great acts of creation. I’ve experimented with it in recent works – to me, AI is humankind’s new crystal ball, playing into our eternal fascination with destiny and divination. It helps us to foresee, foretell, prophesise. It searches for patterns and predicts new ones. It attempts to organise what seems random, providing insight. It’s almost… magic, supernatural, godlike even…?

I often compare art, science and spirituality; all three have the power to inspire awe and wonder. The process of creating a custom AI, and indeed the art of writing good prompts, is also very similar to socially engaged practice; instead of planning and exacting every step it is a collaboration of chance and control, where artist/facilitator and visitor/participant become scientist/explorer, setting up the conditions of an experiment and exploring the possibilities of the space ahead. Together we refine, iterate, eliminate and enhance.

Creating my own GPT gave me more control – however, must be noted that under the OpenAI umbrella the software is still ultimately controlled by venture capitalists. I explored other options including Claude by Anthropic, Midjourney, ‘R’ statistical analysis, ‘A*’ pathfinding algorithm, as well as completely custom software, but with limited skills in software development and the encouragement to self-author, I decided upon ChatGPT 4’s new multi-modal custom GPT toolkit. Although tied to a larger machine, this still allowed me to input my own datasets, combine data and values, find averages, common points, and importantly, to train the AI. It allowed me to train the machine with love and to facilitate a human and more-than-human (animal, insect, machine) collaboration.

You can try the GPT for yourself below, it’s now live in the GPT Store - please note that you will need to sign up for a free account to generate text. To generate images you will need to upgrade to a paid account:

https://chatgpt.com/g/g-Kbd2f1zo1-intuition-maps

And yet…

The GPT is far from perfect; text-wise it’s generally factually accurate but image generation is certainly not - it hallucinates disinformation - and isn’t that the problem with the racist rhetoric around migration? What it doesn’t know or understand it fabricates.

The difference here however is that I’ve attempted to train the machine around a different narrative – one of interconnectedness, compassion and (my idea of) love. Perhaps this will lead to less harmful hallucinations and more positive visions?

But do the facts and the science really change anything anyway? Can they help us to feel..? Intellect alone won’t solve the polycrises. We need intuition, emotion and embodied action.

WAYMARK INTERVENTIONS: SOCIAL SCULPTURE & EMBODIED PRACTICE

Walking is a meditation, a form of resilience, and an act of resistance or defiance.

Process:

Intellectual/emotional – embodied/intuitive – machine/intellectual/emotional – embodied/intuitive – embodied/emotional – embodied/intuitive…

The waymarks, once installed (undergoing yet another reworking of the pattern) will create a legacy of the process and offer a pilgrimage or ritual route, allowing others to walk in the footsteps of the artwork’s multispecies actors, building empathy and solidarity whilst connecting with the more-than-human world.

Both the markers and a simple map leave space, encouraging walkers to tune into their senses, instinct and intuition. This place-based response offers a connection to what has gone before and what is yet to happen.

To encourage interspecies participation, the waymarks also provide sanctuary for one of the referenced local migratory species, the Red Admiral butterfly. Many of these butterflies now choose to overwinter in the UK due to the increasingly milder climate. The neon pink and yellow palette of the waymarks not only serves to punch through the gilded image of the British countryside, but to attract butterflies using colours which they are drawn to, whilst incorporating butterfly-sized slits, creating compass-like patterns on their south-facing sides leading to hollow areas filled with brushwood in which the insects can hibernate. After dark, the waymarks glow under UV light. Many animals, including birds, bees, butterflies and even mammals like reindeer and mice can perceive ultraviolet light.

The iconic waymarks are each hand-crafted from ash – a species common to Irchester Country Park, and associated in mythology with protective, healing properties.

Visitors are invited to trace their own paths through a variety of means and share this data. They are encouraged to play and to continue building on the processes and patterns that have come before, to continue zooming in and out between micro and macro, and to create their own emergent strategies and adaptive systems with the wider ecosystem and each other.

Visitors will get lost, I’m sure of that, but I encourage all participants to forge their own paths with this artwork, whilst respecting the paths chosen by others.

Head here to view the final artwork:

https://www.beccymccray-workwork.com/art-activism/intuitionmaps

WITH THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING RESEARCHER PARTNERS & ADVISORS

Ali Ali, Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at the School of Global Studies, and part of the Sussex Centre for Migration Research

Ian Barker, Ecologist, New Forest National Park Authority

Irchester Country Park rangers

James Pearce Higgins, Director of Science, British Trust for Ornithology

Joel Gethin Lewis, Course Leader, Creative Computing Institute

Johanna Hedlund, PhD Behavioural Ecology, Centre for Ecology and Conservation, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter

Rowan Gard, Lecturer in Human Geography and Sustainability, King’s College London

SPECIAL THANKS TO

All of the participants 🙏

The brilliant James and Abbey at Fermynwoods 💥

The talented Makermark for fabrication and moral support 💗

KEY READING AND RESEARCH:

101221-NERC-LWEC-BiodiversityClimateChangeImpacts-ReportCard2015-English.pdf

AA Easy Read, Britain, 2005 (courtesy of Uncle Tony)

bto_climate_change_and_uk_birds_-_james_pearce-higgins_bto_web-compressed.pdf

David Abrams, Creaturely Migrations essay

Emergent Strategies, Adrienne Maree Brown

England on Fire, Stephen Ellcock

Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape, Mary-Ann Ochota

pub2023-047-l-world-migration-report-2024_6.pdf

Radical Landscapes: Art, identity & activism - TATE

State of the Worlds Migratory Species report_E.pdf

The Book of Trespass, Nick Hayes

The Cosmic Dance, Stephen Ellcock

Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit (with thanks to Becky Horne)